GOOD WORLD / BAD WORLD

A Broad View of Technology's Influence on our Imagination

1. THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Imaginary worlds come to life in so many ways, from analytic thought experiments to religious texts to inscrutable web rings (to name just a few). For these worlds to be constructed in a way that can be shared with others, they must interface with some form of technology. I wrote this essay to better understand the relationship between the tools used in worldbuilding and the resulting work, beginning with three perspectives on technology from the Critical Game Design field informing the PhD program originally compelling this research.

1.1 TECHNOLOGY IS A SYSTEM

“Technology is not the sum of the artifacts, of the wheels and gears, of the rails and electronic transmitters. Technology is a system. It entails far more than its individual material components. Technology involves organization, procedures, symbols, new words, equations, and, most of all, a mindset.”1

This quote is from acclaimed metallurgist Ursula Franklin who defined technology as a system of materials, methods, and cultures. She viewed technology as a process and distinguished between technologies that center individual creators (holistic technologies) and those that organize multi-modal pipelines (prescriptive technologies). Holistic technologies are considered tools and methods of a craft, with the maker fully in control of their process. In the context of contemporary video game production, this would be analogous to an individual building their own game engine within an open-source platform, creating their gameworld from first principles. Prescriptive technologies, on the other hand, evoke an assembly line where makers specialize in their part of the larger process rather than the product as a whole.

In her book “The Real World of Technology”, Franklin draws from her expertise in ancient Chinese metallurgy to illustrate this concept. Back in China’s Bronze Age, the technology for crafting alloy consisted of many complex phases including mining, refining, crafting, and casting. Each step was carried out by different groups of people with specific expertise. However, this technology extended beyond the material processes, involving the social and political organization necessary to coordinate production. The Chinese imperial court held a monopoly on the resources and knowledge required for bronze-making, using this control to maintain social hierarchies. The court determined the design and distribution of bronze objects, which served as symbols of authority and status. Through this lens, Franklin constructs a portrait of a system that entangles tools with socioeconomic and political hierarchies to both produce artifacts and sustain power. As Bruno Latour reminds us, this is the socialization of objects, where technology socializes ideas via object proxies.2

According to Franklin, it is impossible to fully understand ancient Chinese bronze casting technology without considering this broader structure. Extending this example to the context of contemporary game development, we find prescriptive technologies operating in the production of AAA games such as Red Dead Redemption II (Rockstar, 2018). The game's vast open world is created through the coordinated efforts of numerous specialized teams working within a hierarchical structure, each individually responsible for isolated aspects of the game's design, including the generation of its landscapes, characters, stories, and mechanics.3

1.2 THE MEDIUM IS THE MESSAGE

Marshall McLuhan's work in media theory has provided a bevy of juicy platitudes to talk about the relationship between mass media and its influence on culture, as this section’s titular McLuhan aphorism indicates.4 Alongside Franklin, his scholarship provides further context towards examining technology's relationship to mediated worldbuilding today.

Unpacking the aphorism, “the medium is the message”, we find a few important vectors for analysis. The first is an encouragement to study the technology behind the worlds that are built with them. While the content of Red Dead Redemption II shows one portrait of a fantasy cowboy world, understanding its relationship to the technology that birthed it provides a different understanding of that world including the labor conditions that produced it, the previous media that influenced it, and the worldview of its creators.5 Secondly, it is important to understand how a form of communication both alters its content and provides preferential treatment to certain signals. As articulated by Media theorist John M. Culkin,

“Linguists tell us it's possible to say anything in any language if you use enough words or images, but there's rarely time; the natural course is for a culture to exploit its media biases.”6

Third, it is important to recognize how media shapes individuals and societies. McLuhan saw all technology as extensions of ourselves, going so far as calling any new technology a “self-amputation”7 of our physical bodies in the way they demand us to recalibrate how we interact with our environment and each other. The wheel extends the foot, clothing extends the skin, and electronic media extends the nervous system. Creators like those that produced the worldbuilding works discussed in this essay, through McLuhan’s lens, can be interpreted as interoperable information forms whose nervous systems were long ago amputated and translated into a web of technological consciousness that both comprises and interprets the technology process. We form the technology and the technology forms us.

1.3 ACTION POSSIBILITIES

Don Norman’s concept of affordances provides this essay with one final framework for examining the relationship between technology and its artifacts. In his influential book "The Design of Everyday Things", Norman defines affordances as the action possibilities of an object.8 A hammer affords (is for) hitting. A pencil affords mark-making. A camera affords image-capturing. From a user-centered design perspective, an understanding of affordances helps designers create objects that effectively communicate their intended use. Signifiers, the qualities of an object or system that convey their affordances, provide cues that suggest appropriate uses. By examining what signifiers are designed into a technology, we can better understand what modes of expression various tools are designed to readily afford. Moreover, understanding affordances allows us to recognize the limitations of certain tools in a creative practice, shedding light on the boundaries of what ideas can be readily expressed.

Worldbuilding is a complex and multifaceted process that often involves the use of a diverse array of tools. The design of those tools significantly influences what can be easily created with them, ultimately shaping the content produced. To explore this relationship further, the following two sections compare a selection of worldbuilding projects, investigating how the tools and technologies employed in their creation have a discernible impact on the resulting imaginary worlds.

2. WORLDS WITHIN WORLDS

Two vectors frequently used to evaluate the quality of a media object’s worldbuilding are their completeness9 and consistency.10 An evaluation of a media world's completeness assesses the level of explanation and detail that coheres into a feasible whole with the understanding that gaps will always remain. An analysis of consistency, on the other hand, considers the relationship between elements comprising the world, looking for any contradictions.

In these terms, bad worldbuilding refers to a media object's distracting gaps and disconnected elements that may suggest a creator's incompetence. Conversely, good worldbuilding evokes a sense of seamlessness, allowing the user to relate to the secondary world in a way that resembles their relationship to the primary world. This sense of immersion is crucial for engaging with imaginary worlds. However, there is also a form of bad worldbuilding that approaches high levels of completeness and consistency too literally. In a controversial essay pointing a critical gaze at literary worldbuilding, author Lincoln Michel wrote:

“The goal of the writer is not to clutter the path with every object they can think of, but to clear the way for the reader’s journey.”11

Because literature is traditionally a linear narrative medium, Michel objects to superfluous details that might create an encyclopedic literary sensibility and distract readers from the core vectors of the book. M. John Harrison, another critic who warns authors against rigid worldbuilding impulses, claims that bad worldbuilding undercuts the most exciting aspects of fiction: the necessity for the reader to actively engage their imagination to fill in the textual gaps. It is impossible to perfectly replicate the world through symbols; writers can only imply or allude to it. Even if it were possible to fully encode the world into language, the reader would not be able to decode it with meaningful precision due to the diffused clutter pointed out by Michel. Good literary worldbuilding, according to Harrison, is not an operating manual for a fictional world. It leverages the gaps inherent to writing:

“Since a novel is not an object of the same order as a vacuum cleaner, and since the ‘world’ a worldbuilder claims to build does not in fact exist in the way a vacuum cleaner exists, why would you want to try & operate it as if it was one ?”12

In these terms, William Gibson's "Neuromancer" stands as an example of effective literary worldbuilding. Widely regarded as the seminal work of the cyberpunk genre, Gibson's 1984 novel presents a dystopian future shaped by advanced computer technologies. However, the world is not presented as a fully realized encyclopedic construct. Rather, Gibson conjures an imagined future through evocative prose that leverages tropes from hardboiled detective fiction. The novel is characterized by a sparse, poetic style rich with neologisms and technical jargon demanding active engagement for sense-making, drawing into focus the implications of its invented technologies on the human experience. While there is a ludic aspect to this sense-making, Gibson distinctly approached “Neuromancer” as a literary world, not a gameworld. In a 2014 interview about literary worldbuilding, Gibson shared the following:

“I remember these guys turned up from RPG company after Neuromancer came out - they wanted to make a game. They set me down and questioned me about the world. They asked me where the food in the Sprawl comes from. I said I don’t know. I don’t even know what they eat. A lot of krill and shit. They looked at each other and said it’s not gameable. That was the end of it. The Peripheral is not gameable. It has a very high resolution surface. But it’s not hyperrealistic down into the bones of some imaginary world. I think that would be pointless. It would be like one of those non-existent Borgesian encyclopedias that describe everything about an imaginary place and all of it is self-contradictory.”13

2.1 CYBERTEXTUAL WORLDS

The engagement with literary worlds inherently involves a playful aspect, stemming from the complex process of interpreting textual imaginaries. However, some forms of literary worldbuilding take this ludic quality further, actively incorporating it into the reading experience through more explicit interactive elements. This approach aligns with what Espen Aarseth termed "ergodic literature" in his 1997 book "Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature". Aarseth defines cybertexts as follows:

The concept of cybertext focuses on the mechanical organization of the text, by positing the intricacies of the medium as an integral part of the literary exchange… During the cybertextual process, the user will have effectuated a semiotic sequence, and this selective movement is a work of physical construction…”14

While all readers engage in mental world-construction, cybertexts introduce an additional layer of physical interaction. Readers of cybertexts not only mentally construct the literary world but also actively manipulate the text to navigate its logical structure. This dual engagement - mental and physical - often lends cybertextual worlds a more explicitly interactive or game-like quality.

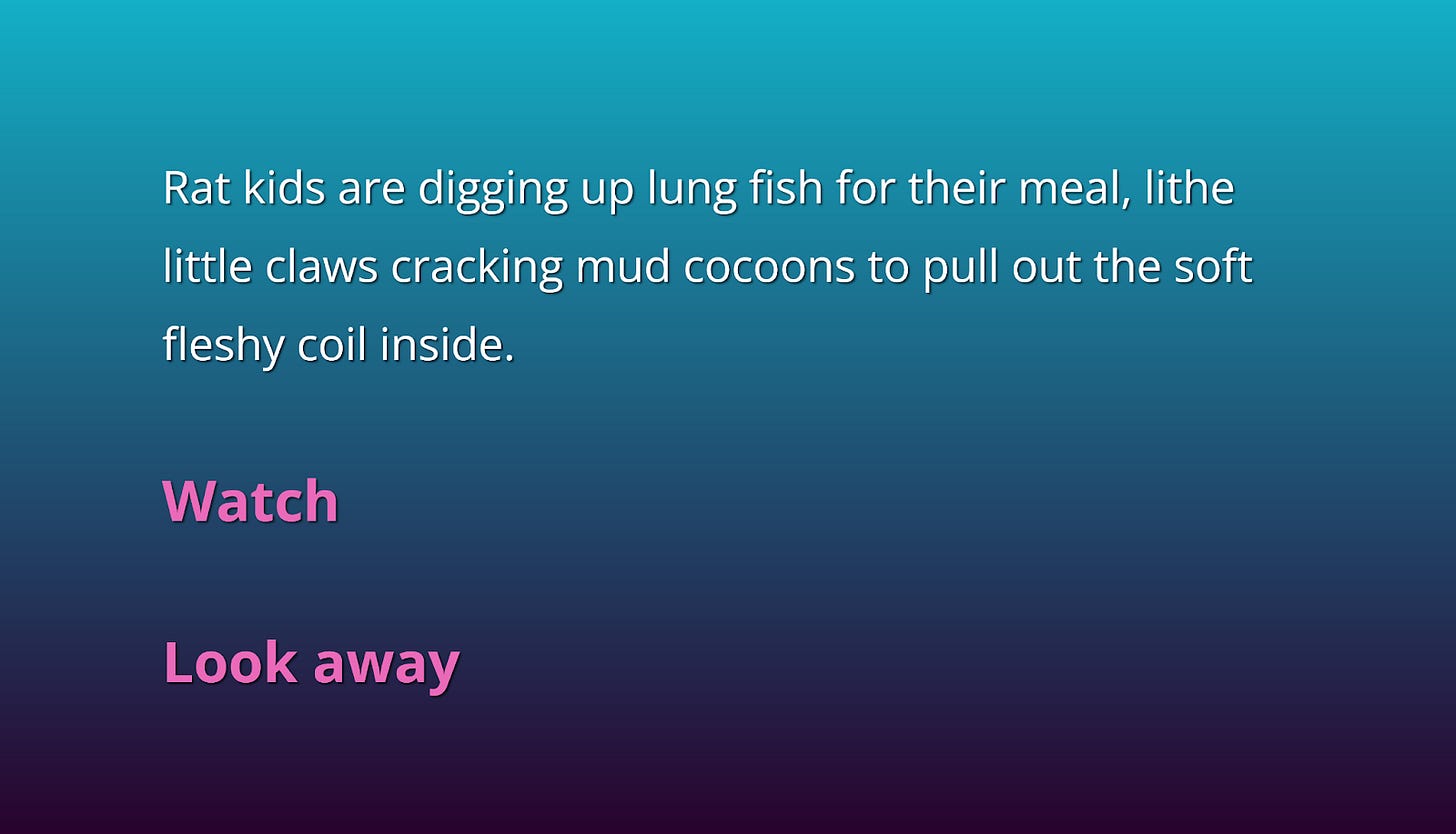

Porpentine’s Twine game, “With Those We Love Alive” serves as an illustration of good worldbuilding in this domain. The game opens simply with a <3 emoticon that changes color when a computer mouse hovers over it. Clicking on this heart-shaped icon brings the reader to a set of instructions requesting they have a drawing implement nearby. As the player continues to click through descriptions of a vague dystopian realm ruled by a monstrous empress, they are invited to select texts that compel their avatar to act and explore while occasionally being prompted to draw sigils on their actual skin. In this way, traversal of this literary gameworld augments the act of reading with a series of embodied traces: temporary tattoos designed to mark acts of complicity and resistance against the oppressive systems presented there. The effectiveness of Porpentine's worldbuilding has been praised by game critics such as Alice O'Connor, who noted how “With Those We Love Alive”:

“... invited me to fill in the rest of its world with mine. I can close my eyes and see the canal and the rat kids scratching for lungfish, snatches of London, Paris, and, curiously, Dark Souls.”15

2.2 WORLD EXPANDING PARATEXTS

One final piece of textual worldbuilding that significantly influences the scope and depth of literary worlds is their paratexts. This term, coined by Gerard Genette in his 1987 book “Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation” describes those elements that exist alongside the printed book and influence the reader’s understanding of that which is embedded in the text. For Genette, this includes components such as the table of contents, index, and title. Games scholar Mia Consalvo later expanded the meaning of Genette’s term in the context of video games to consider a broader constellation of texts that include strategy guides, instruction manuals, and magazines.16

Growing up in the eighties, I was enamored with all manner of imaginary worlds. Lacking the technology to engage with much more than textual ones, paratexts played a crucial role in my engagement with gameworlds. Many years before I had home access to video games, I subscribed to game magazines, beginning with “Nintendo Fun Club News” which would later become “Nintendo Power”. This magazine was primarily a promotional tool for Nintendo, sharing news of current and future products in a richly illustrated format.17 It also featured game guides, shaping player expectations through a variety of paratextual materials. These guides often explained the game's basic story, gave character background, and offered visually-detailed tableaus of environments, items, monsters, and more. They varied in style, but shared a consistent design template, creating a sense of cohesion for each gameworld unto itself. For those who had access to a Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), Nintendo Power helped augment the construction of the gameworld in their imagination as the fidelity of that system’s graphics was limited. For an eight year old like myself who had no NES but was enamored with the promise of executing flashy martial arts maneuvers to beat up someone called Shadow Boss, the paratexts around Double Dragon (Technōs, 1987) were a central experience of that world. Without ever touching the actual Nintendo, I immersed myself in this imaginary world for many years through descriptions, illustrations, and elaborations from a single eight-page guide.18

3. COMPUTER WORLD

The rising popularity and accessibility of computer technology like the NES ushered in a new era of worldbuilding in the late twentieth century that opened new forms of invention. For one, computers enable world elements to be presented without a predetermined beginning or end, allowing for the manifestation of worlds as databases rather than stories. These nonlinear data structures provide multiple points of entry and exit, catering to the encyclopedic impulse of many worldbuilders who M. John Harrison and Lincoln Michel would criticize in a linear literary mode. This database mode of worldbuilding, however, has new purchase in a technology landscape where vast amounts of data are effortlessly stored, sorted, searched, simulated, and visualized. In the process of facilitating this new approach to worldbuilding, however, computers leave their marks on the worlds built within them, shaping these imaginary realms in ways that reflect the history and material of the technology itself.

3.1 THE SURFACE OF THINGS

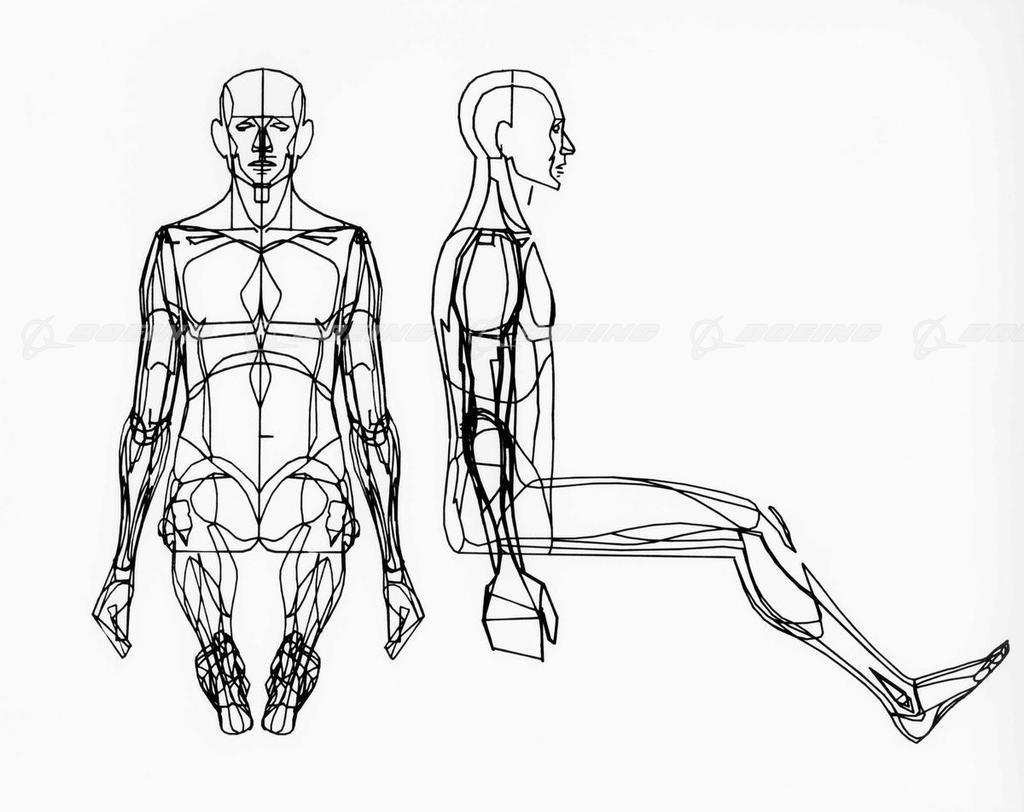

Prior to their commercialization, computers were mainly used for processing numerical data on large mainframes designed to solve predetermined problems, such as calculating missile trajectories.19 Non-numerical visualizations were eventually developed to enhance the legibility and usability of these problem solving processes through graphical interfaces. By the sixties, technologists were beginning to devise ways of using the computer to simulate fully dimensional objects in the virtual space of the computer itself. The first 3D human-computer figure was developed in 1964 at the Boeing Airplane Company, giving birth to the term Computer Graphics (CG). This virtual object was initially named "First Man'' by its creator William Fetter and later canonized with traces of its industrial genesis as "Boeing Man".

3D modeling an object like Boeing Man typically involves using software to manipulate points in virtual space that form a mesh. The object's shape is defined by its vertices, edges, and faces, while its surface is determined by computational textures and materials that control properties such as color, reflectivity, and transparency. Since the creation of Boeing Man, whose form was derived from U.S. Air Force pilot measurements and converted into CG using punch cards, 3D modeling tools have advanced significantly, offering a range of interpretative options to worldbuilders.20 Still standard to the 3D modeling process, however, is the empty world creators build within.

Virtual space for 3D modelers traditionally starts with a mass-less point in a void, representing the world-origin. This visible address allows for easy orientation and seamless interchangeability between programs, facilitating the movement of 3D objects in and out of the environment. Within this empty space, modelers create geometries composed of polygons - three or more points connected by lines and filled in to form a surface. These polygonal surfaces connect and accumulate to develop representational geometries, mathematical constructions of hollow objects. As audiences, we might perceive a sense of weight to these objects, but they are nonetheless empty and weightless, birthed in an addressable cartesian void.

Pixar’s breakout feature film “Toy Story”, widely celebrated for its innovative technological worldbuilding, was the first 3D CG world I deeply engaged with as a viewer. It emerged from the work of John Lasseter whose first foray into computer modeling was an attempt to recreate his desk lamp at work, which later became the star of Pixar's second animated film, "Luxo Jr". Lasseter's approach to building a world around an animate desk lamp was inspired in part by his appreciation for Walt Disney’s animation, who demonstrated the potential of anthropomorphized inanimate objects to provoke drama when set in motion.

The affordances of the nascent RenderMan21 software Lasseter was using to test its photorealistic capabilities are also apparent, given how primitive geometries with hard reflective surfaces were the most readily producible objects in that technology paradigm. The choice of a simple, geometric object like a desk lamp allowed Lasseter to showcase the software's ability to create convincing, lifelike animations while working within the constraints of the available technology.

Lasseter’s next two films, “Red’s Dream” and “Tin Drum” continued to push PIXAR’s CG capabilities, but the company quickly discovered the technology's limitations. In describing the production process of “Tin Drum”, members of PIXAR’s animation team struggled with how the baby human in that film proved extremely difficult to animate:

“‘It just became an incredible burden,’ remembered Flip Phillips, a new member of the team at the time. In early attempts at a model of the baby’s head, he appeared to have the face of a middle-aged man. The final version of the baby (known to the team as Billy) had a much-improved face, but his skin had the look of plastic. When he moved, moreover, his body lacked the natural give of baby fat and his diaper had the solidity of cement - compromises made necessary by lack of time and the still-developing technology. Lasseter and his technical directors slept under their desks.”22

As PIXAR’s more contemporary feature film examples like “Lightyear” demonstrate, including baby fat and diapers in a 3D CG world no longer work against the affordances of the technology. RenderMan has been consistently revised and updated over the past three decades to allow for this type of world construction. However, in the early nineties computational limitations were palpable, consequently encouraging Lasseter to return to earlier tests with inanimate objects to conceive of PIXAR’s breakout world of “Toy Story”.

In contrast to the hard-surface modeling encouraged by PIXAR’s RenderMan technology in the nineties, photogrammetry allows worldbuilders to approach the construction of 3D CG worlds from a different angle resulting in a different set of affordances. Instead of emanating from a cartesian void, photogrammetry emerges from an existing environment, using tools to capture and remap existing target objects into virtual space. These 3D objects are not hollow; they are clouds of visual data pregnant with details from the real-world objects they represent.

The Vanishing of Ethan Carter (The Astronauts, 2014) is a video game that has garnered significant critical acclaim for its innovative approach to technological worldbuilding. Created by a team of three developers, the game employs photogrammetry, utilizing high-resolution photographs of real-world objects and environments, to create their CG world. By leveraging this technology, the developers were able to construct a highly detailed 3D video game environment that challenged preconceived notions of what a small team could achieve in a gameworld.23

The game’s designer, Adrian Chmielarz, articulated how they approached worldbuilding in a naturalistic way:

“We stole from nature itself. When you create game levels using your imagination, no matter how talented your artists are, these levels still feel a bit artificial. More like a spectacular movie set than a real place. And since our game is all about immersion and the feeling of presence, we decided to copy entire acres of land into the game. Most of Ethan was shot in the Karkonosze mountains here in Poland. What also helped was this magical tech called photogrammetry. In short, you take dozens of photos of an object, put them into this special software, and an hour later it spits out a nice, game-ready 3D object.”24

Chmielarz demonstrated how CG could be approached differently than traditional graphics paradigms at the time to create a gameworld through techniques that eschewed precise surface modeling. Instead, these worlds imported fragments from the creators' own home environment into a new virtual space - a process of CG bricolage – a term introduced by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in his book "The Savage Mind" to describe the act of creating something new by repurposing readily available materials. Sherry Turkle, in her book “Life On Screen” extended this concept into the digital domain:

“Problem-solvers who do not proceed from top-down design but by arranging and rearranging a set of well-known materials can be said to be practicing bricolage. They tend to try one thing, step back, reconsider, and try another. For planners, mistakes are steps in the wrong direction; bricoleurs navigate through midcourse corrections. Bricoleurs approach problem-solving by entering into a relationship with their work materials that has more the flavor of a conversation than a monologue. In the context of programming, the bricoleur’s work is marked by a desire to play with lines of computer code, to move them around almost as though they were material things.”25

Turkle highlights the value of a softer style of bottom-up design in contrast to more rigid top-down approaches,26 calling for an emphasis on tinkering with world components instead of designing rules in advance to follow during construction. This approach embraces the phenomenon of emergence in which the interaction of relatively simple elements results in meaningful situations created by neither designer nor computer, a unique affordance of automated technologies many CG worldbuilders embrace.

3.2 PROCEDURAL GENERATION

“Simple rules lead to complex behavior. Complicated rules lead to stupid behavior.”27

Extrapolating from this quote by software engineer Andrew Hunt, good worlds are complex, not complicated. They are built upon simple rules that can be shared between many world components, creating conditions for emergence that bricoleurs often leverage to engage with those worlds. Emergence, a foundational bottom-up phenomenon, is often impeded by overly premeditated master plans. Simpler world designs make those worlds more predictable, allowing users to more readily conjure idiosyncratic scenarios that designers would have never predicted in advance. As Hunt's insight suggests, this is an important vector for consideration when evaluating the design of procedurally generated (proc-gen) worlds.

in her influential essay “So You Want to Build a Generator”, game designer Kate Compton offers a framework to those interested in building highly emergent worlds. Unlike traditional literary worldbuilding where creators evoke a single ground truth version of the world in writing, Compton encourages designers to articulate both good and bad versions of their world components to conceive a possibility space the two. With this range in mind, she encourages designers to prototype and tinker, revising the underlying rules of their world to generate more preferable world elements and less unwanted ones using a trial-and-error approach with pre-existing generative algorithms.

Compton’s bricoleur framework embraces prescriptive technologies inherent to personal computing technologies - omnibus devices designed to do everything from balancing budgets to calculating missile trajectories to reconnecting with childhood friends living across an ocean. When using this technology for worldbuilding, Compton’s advice is to overproduce and refine for perceptual uniqueness:

“So your algorithm may generate 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 planets. They may each be subtly different, but as the player is exploring them rapidly, will they be perceived as different? I like to call this problem the 10,000 Bowls of Oatmeal problem. I can easily generate 10,000 bowls of plain oatmeal, with each oat being in a different position and different orientation, and mathematically speaking they will all be completely unique. But the user will likely just see a lot of oatmeal. Perceptual uniqueness is the real metric, and it's darn tough.”28

In the early nineties, artists like John Lasseter and his generation of worldbuilders grappled with the limitations of 3D CG tools built for creators to hand-model every detail of an object’s surface. Over years of development, they found workaround solutions to create worlds that appeared consistent and complete. They developed techniques that compensated for their computers’ limited ability to create the worlds they wanted. Compton shows us how artists can create similar workarounds to approach proc-gen worlds, encouraging creators to focus on the perceptual surface experience of their imaginary world to obfuscate the constraints of its underpinnings. As she put it:

“In some situations, just perceptual differentiation is enough, and an easier bar to clear… Perceptual uniqueness is much more difficult. It is the difference between being an actor being a face in a crowd scene and a character that is memorable. Does each artifact have a distinct personality? That may be too much to ask, and too many for any user to remember distinctly. Not everyone can be a main character. Instead many artifacts can be drab background noise, highlighting the few characterful artifacts.”29

This approach is well demonstrated in gameworlds such as No Man’s Sky (Hello, 2016), an ecosystem of 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 proc-gen planets designed for players to discover and explore. Geographically speaking, No Man’s Sky is measurably the largest imaginary world ever conceived, but upon its release in 2016 almost every location in this world had no legible histories, stories, or other characteristics traditionally considered good worldbuilding.30 Commenting on criticism of the game’s “10,000 bowls of oatmeal” problem, Compton reflected on lessons she learned during her own development experience of the proc-gen video game Spore (Maxis, 2008):

"We got that the big challenge was technical, and we thought if all the procedurally generated stuff worked, we would win … But after the technical challenge is complete there's this whole other challenge of making it meaningful."31

So how do proc-gen worldbuilders make their worlds meaningful? To address this question, let’s look at one final computational worldbuilding example: Minecraft (Mojang, 2011). Originally designed by Markus Persson, also known by the nickname Notch, Minecraft is made of approximately 1.35 x 1018 blocks representing 37,282 miles of traversable space.32 Not as big as No Man’s Sky, but still large: over three times the size of the planet Earth. As games like Spore and No Man’s Sky demonstrate, however, infinite space does not equal infinite possibility. Large worlds can feel empty. In consideration of this, Minecraft was designed to invite its audience to help define the world’s possibility space. As articulated by media scholar Dennis Redmond:

“Minecraft is a commercial franchise wrapped around a core noncommercial fan community. While the fan community does not legally own the franchise, this lack of formal ownership is also irrelevant. The reason is that fans co-produce, co-regulate, and co-distribute the videogame in close concert with the commercial franchise.”33

While Minecraft has its origins in gameworld design principles shared by Spore and No Man’s Sky, it grew into a different world that is widely considered a benchmark for good proc-gen worldbuilding through its embrace of social emergence. Unlike literary worlds that originate in narrative form, Minecraft originated in the form of worldbuilding itself. Through YouTube videos, comics, musical albums, and articles, Minecraft leverages its community’s worldbuilding engagement, continuing to expand through a constellation of media fragments across a distributed database. Microsoft, the current proprietors of the Minecraft world, extended Mojang’s emergent design philosophy beyond the imaginary world itself, consequently inviting its audience to fill in its infrastructural gaps with their own stories, characters, mythologies, and philosophies. Worlds are leaky, and Minecraft discovered a way to embrace that quality thereby setting a precedent that other gameworlds like Fortnight (Epic, 2017) continue to experiment with and push into future benchmarks - the creation of a metaverse that explicitly blurs world boundaries with their own world at its center.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this essay I explored some media objects and the way their technological construction influenced them, focusing on a continuum that ranges from narrative literary worlds to ludic computer worlds in terms of their worldbuilding. Initially, I intended this essay to trace the boundaries of a much broader sphere of influence. However, I narrowed my focus to examine the effects of technology pertinent to the discourse I have encountered during my first two years in the Games and Simulation Arts and Sciences program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Originally written as a qualifying exam, my aim was to adhere to the formal constraints of a single paper. Looking to the future, I want to conclude by highlighting the further research and writing I intend to produce across interdisciplinary spectrums beyond those constraints.

4.1 FUTURE TECHNOLOGY

The term metaverse colloquially refers to a virtual world designed for multiple users to interact with each other. The term was coined by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 cyberpunk novel “Snow Crash” denoting a virtual reality space accessed through the internet where users, represented as avatars, interact with each other and computer-generated environments. Stephenson’s original conception of this world was a wry dystopian one:

“The sky and the ground are black, like a computer screen that hasn't had anything drawn into it yet; it is always nighttime in the Metaverse, and the Street is always garish and brilliant, like Las Vegas freed from constraints of physics and finance.”34

In a move that underscores the growing influence of science fiction on contemporary technological development, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of the company formerly known as Facebook, rebranded his corporation as Meta in 2021, rhetorically bringing Stephenson’s metaverse concept into the realm of commercial reality. As part of this initiative, Meta began the development of Horizon Worlds, a virtual reality platform that aims to provide a new interpretation of Stephenson's original vision. Zuckerberg’s metaverse is a world where you don a headset and spend your life doing things you could otherwise only do if you were extremely rich.35 His transformation of a well-known cyberpunk dystopia into a celebration of capitalist excess marks a troubling moment in the history of capitalism. Wealthy tech entrepreneurs are drawing inspiration from worlds that once served as an indictment of the very system they now perpetuate.36

As an artist actively building worlds with tools developed by these entrepreneurs, I often think about my role in the process of technology and its output. Every time I hear the term AI uttered as a catch-all phrase to describe technologies most of us only understand on their surface, it reminds me of this complex back and forth between worldbuilders' intentions and their actual legacies. It compels me towards conceiving and documenting new forms of critical worldbuilding that actively leverage technologies that are part of one imaginary world, such as that described by Zuckerberg, to develop unstable experimental worlds that complicate the feedback loop between technology and its many subcreations.

4.2 IDEOLOGY

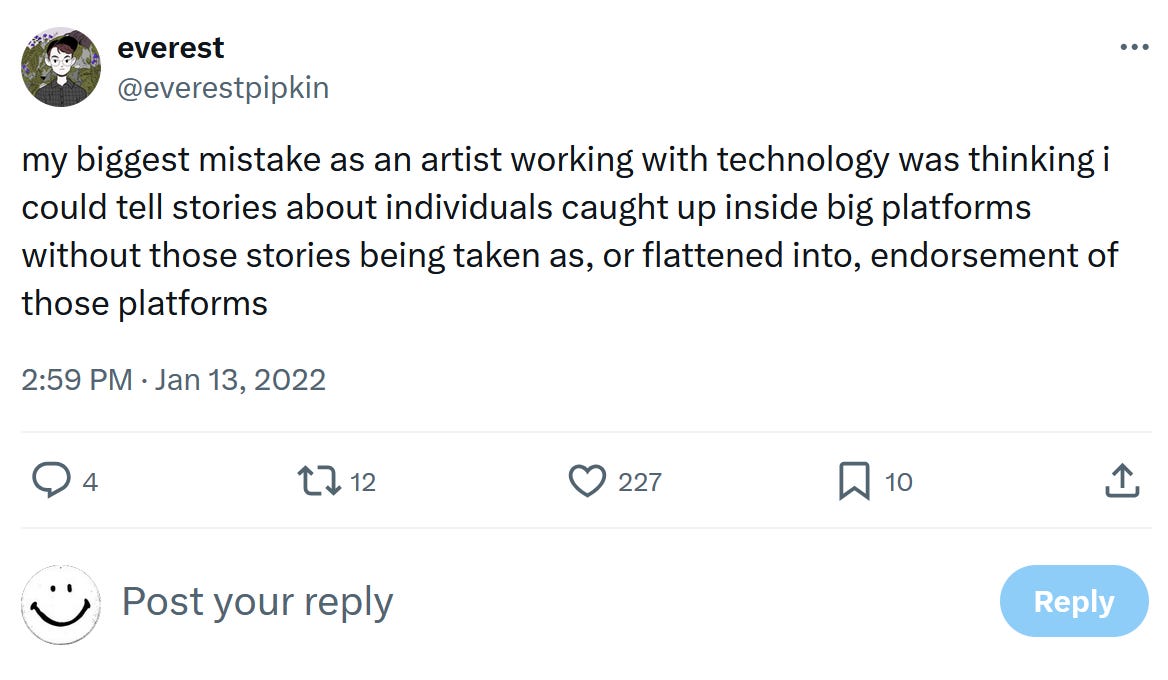

When immersed in the process of digital worldbuilding, there are moments when I stop experiencing my tools as alien inputs and engage with them as bodily extensions – they become ready-to-hand in a Heideggerian sense.37 Having worked with digital worldbuilding tools for over three decades, starting with the Apple IIe computer platform, I recall countless times when this was not so. In fact, this past year while teaching myself how to use Epic Game’s Unreal Engine for worldbuilding, I spent months fighting against it, experiencing it as foreign and present-at-hand. In this process, I was acutely aware of Epic Game's technical ideologies that were discordant with my own. Now, six months later, actively using Unreal Engine to create a feature film, I have a different relationship with this game engine. I no longer notice it as foreign; I've assimilated into the technology and its ideologies through the aesthetic and mechanical decisions I make within the engine. This dynamic, as observed by artist Everest Pipkin, creates a flattening effect:

Due to space constraints, I did not attempt to broach this topic of ideology and its relationship to digital technology – the implicit assumptions embedded in countless lines of code that shape trends across cultural spheres.38 I am interested in the way ideologies behind technologies get propagated in worlds that are built with them. For example, shifting my use of Unreal Engine from developing a subtle film about a fractured friendship to building a bombastic first-person shooter, I find it easier to create violent gun mechanics than melancholic scenes of men discussing their sadness around aging. The foundations of these tools, as discussed in this paper, are apparent through the types of experiences they more readily produce. I wonder how that recognition may be further expanded and leveraged in a practice of critical worldbuilding.

4.3 FUTURE WORK

I take inspiration from Mark Fisher’s concept of world-hemorrhaging39, the idea that certain worlds can be made ontologically unstable, allowing their creators to fracture them into multiple versions that unsettle existing narratives. David Lynch is one example of a world-hemorrhager. In his television series “Twin Peaks” there is a zone called the black lodge, a supernatural space designed to disorient its viewers alongside the fictional cast of “Twin Peaks”. This disorientation remains somewhat superficial, however, as it is justified according to the diegetic logic of the show. When this diegesis is troubled, as Lynch did in the third season of Twin Peaks through recasting key characters in new roles with different affects, it renders the show’s previous logic incoherent and thereby problematized the entire world framework. 40 A much more profound destabilization occurred.

Worldbuilding is a process of twinning - of exploring the double exposure between the real and the imaginary. I am interested in the way worldbuilding can function as a subversive practice when previously established coherences are problematized and undermined as many creators of afrofuturist, ecofeminist, and solarpunk worlds aim to demonstrate. What could be the current metaverse’s version of afrofuturism? What would Zuckerberg’s third season of “Horizon Worlds” look like?41

Due to space constraints, this paper could not fully explore the impact of linear time-based technologies on worlds like those created by Lynch, thereby eliminating a broader discussion of technology's temporal influence on worldbuilding. In Andrei Tarkovsky’s book “Sculpting in Time”, he wrote about the filmmaking process as one of constructing and manipulating the flow of time to create new meanings and associations. Tarkovsky emphasized the importance of the time-pressure within a shot, the sense of rhythm and duration that can be created through the careful composition and juxtaposition of images. In the context of worldbuilding, that time-pressure can be leveraged to build dream worlds that I call “Zones” after Tarkovsky’s 1979 film “Stalker”. In that film, the Zone exists as a liminal geographic space cordoned-off from the rest of the world by a military presence and big fences. Within the Zone, reality is incoherently warped by mysterious forces and the characters who dwell within operate in heightened emotional states. Burning Man42 was inspired by this world. The meltdown at Chernobyl uncannily reflected it.43 More and more, media worlds reproduce their own versions of it.

Zones spatially manifest a sense of wonder that emerges through a process of world-estrangement many scholars have argued is necessary for audiences to penetrate the veneer of fiction around most imaginary worlds. Viktor Shklovsky called this process defamiliarization.44 Bertold Brecht’s word for it in theater was alienation.45 J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary version was recovery.46 In a world where Frederic Jameson’s aphorism that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism resonates with growing audiences, building critical zones that attempt to penetrate the veneer of dominant ideology is increasingly crucial. 47 I look forward to continuing to attempt that puncture. I’m curious what would leak out.

5. REFERENCE

1. Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

2. Boluk, Stephanie, and Patrick LeMieux. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

3. Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and translated by John Willett. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964.

4. Bucknell, Alice. "Second Life’s Loyal Users Embrace Its Decaying Software and No-Fun Imperfections." Document Journal, 2024. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.documentjournal.com/2024/05/second-life-virtual-world-gamer-furry-identity-world/.

5. Carlson, Kara. "At SXSW, Mark Zuckerberg Says Metaverse is ‘Holy Grail’ of Social Experience." Austin American-Statesman, 2022. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.statesman.com/story/business/2022/03/16/sxsw-facebooks-mark-zuckerberg-says-metaverse-future-internet/7051230001/.

6. Cheng, Ian. Emissaries Guide to Worlding. London: Serpentine Galleries, 2018.

7. Compton, Kate. “So You Want to Build a Generator.” 2016. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.tumblr.com/galaxykate0/139774965871/so-you-want-to-build-a-generator.

8. Conway, John. “The Game of Life.” Scientific American 223, no. 4 (1970): 4.

9. Consalvo, Mia. Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

10. Cruinne. “Things Worlds Have.” Arcadia.net. 2013. Accessed November 9, 2023. http://arcadia.net/Cruinne/DnD/Articles/worldbuilding.html.

11. Culkin, J.M. “A Schoolman’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan.” Saturday Review, March 18, 1967, 51-53.

12. Doležel, Lubomír. Heterocosmica: Fiction and Possible Worlds. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

13. Ellis, Warren. “M John Harrison On Worldbuilding.” 2007. Accessed November 9, 2023. http://www.warrenellis.com/?p=4136.

14. Fisher, Mark. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater Books, 2016.

15. Fizek, Sonia. Playing at a Distance: Borderlands of Video Game Aesthetic. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022.

16. Franklin, Ursula. The Real World of Technology. Toronto: House of Anansi, 2004.

17. Gaboury, Jacob. Image Objects: An Archaeology of Computer Graphics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

18. Garrelts, Nate. Understanding Minecraft: Essays on Play, Community and Possibilities. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014.

19. Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

20. Goldberg, Harold. "How The West Was Digitized: The Making Of Rockstar Games’ Red Dead Redemption 2." Vulture, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/the-making-of-rockstar-games-red-dead-redemption-2.html.

21. Goodrich, Joanna. "The Story Behind Pixar’s RenderMan CGI Software." IEEE Spectrum, 2024. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://spectrum.ieee.org/story-behind-pixars-cgi-software.

22. Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.

23. Jameson, Fredric. The Seeds of Time. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

24. Jenkins, Henry. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” In First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan, 118-130. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

25. Jenkins, Henry. “Building Imaginary Worlds: An Interview with Mark Wolf Parts 1-4.” 2013. Accessed November 9, 2023. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2013/09/building-imaginary-worlds-an-interview-with-mark-j-p-wolf-part-one.html.

26. Latour, Bruno. “Where are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, edited by Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law, 225-258. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

27. Lepore, Jill. "Elon Musk is Building a Sci-Fi World, and the Rest of Us Are Trapped in It." New York Times, 2021. Accessed November 4, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/opinion/elon-musk-capitalism.html.

28. Maiberg, Emanuel. “No Mans Sky’ Is like 18 Quintillion Bowls of Oatmeal." Vice, 2016. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.vice.com/en/article/nz7d8q/no-mans-sky-review.

29. Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

30. McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Northampton, MA: Tundra Publishing, 1993.

31. McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis H. Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

32. Michel, Lincoln. "Against Worldbuilding." Electric Literature, 2017. Accessed September 5, 2021. https://electricliterature.com/against-worldbuilding/.

33. Morris, Holly. "The Stalkers." Slate, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/09/the-stalkers-inside-the-youth-subculture-that-explores-chernobyls-dead-zone.html.

34. Neofetou, Daniel. Good Day Today: David Lynch Destabilizes the Spectator. Alresford: Zero Books, 2012.

35. Newitz, Annalee. "William Gibson On The Apocalypse, America, and The Peripheral’s Ending." Gizmodo, 2014. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://gizmodo.com/william-gibson-on-the-apocalypse-america-and-the-peri-1656659382.

36. Nintendo. "Nintendo Power." Issue 1, July/August 1988.

37. Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

38. O’Connor, Alice. "Physically Interactive Fiction: With Those We Love Alive." Rock Paper Shotgun, 2014. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/drawing-violences-mundanity-with-those-we-love-alive.

39. Porpentine. With Those We Love Alive. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://xrafstar.monster/games/twine/wtwla/.

40. Price, David. The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Vintage, 2009.

41. Reeves, Ben. "Afterwords – The Vanishing of Ethan Carter." Game Informer, 2014. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2014/10/24/afterwords-the-vanishing-of-ethan-carter.aspx.

42. Roine, Hanna-Riikka. Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements: The Rhetoric of Worldbuilding in Contemporary Speculative Fiction. Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2016.

43. Ryerson, Liz. "The California Problem." Ellaguro (blog), February 2023. Accessed February 1, 2024. http://ellaguro.blogspot.com/2023/02/the-california-problem.html.

44. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

45. Sarkar, Samit. "Does Red Dead Redemption 2 Contain a Hidden Reference to Developers’ Crunch?" Polygon, October 29, 2018. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.polygon.com/2018/10/29/18039824/red-dead-redemption-2-crunch-overtime-rockstar-games.)

46. Shklovsky, Viktor. Theory of Prose. Translated by Benjamin Sher. Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990.

47. Sheff, David. Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. New York: Random House, 1993.

48. Stephenson, Neal. Snow Crash. New York: Bantam Books, 1992.

49. Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-Stories.” In The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, edited by Christopher Tolkien, 109–161. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1983.

50. Troemel, Brad. "PASTEL HELL: The Definitive Guide to Millennial Aesthetics." YouTube, uploaded by Brad Troemel, November 25, 2020. Accessed May 22, 2024.

51. Tufekci, Zeynep. "The Real Reason Fans Hate The Last Season Of Game Of Thrones." Scientific American, 2019. Accessed October 2024. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-real-reason-fans-hate-the-last-season-of-game-of-thrones/.

52. Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

53. Walker, John. "Wot I Think: The Vanishing of Ethan Carter." Rock Paper Shotgun, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/wot-i-think-the-vanishing-of-ethan-carter.

54. Weisenburger, Kirsten. "Enter The Zone – Episode 1: How a Band of Pranksters Inadvertently Created Burning Man." Journal of Burning Man, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://journal.burningman.org/2021/08/black-rock-city/building-brc/zone-episode-1-how-pranksters-created-burning-man/.

55. White, Sam. "Red Dead Redemption 2: The Inside Story Of The Most Lifelike Video Game Ever." GQ, 2018. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/red-dead-redemption-2-interview.

56. Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950.

57. Wilde. “Ten Authors on the ‘Hard’ vs. ‘Soft’ Science Fiction Debate.” Tor.com, 2017. Accessed November 9, 2023. http://www.tor.com/2017/02/20/ten-authors-on-the-hard-vs-soft-science-fiction-debate/.

58. Wolf, Mark J.P., and Bernard Perron, eds. The Video Game Theory Reader. New York: Routledge, 2003.

59. Wolf, Mark J.P. Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation. London: Routledge, 2012.

60. Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. The Routledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds. New York: Routledge, 2018.

61. Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. Revisiting Imaginary Worlds: A Subcreation Studies Anthology. New York: Routledge, 2019.

62. Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. World-Builders on World-Building An Exploration of Subcreation. New York: Routledge, 2020.

63. Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. Exploring Imaginary Worlds: Essays on Media, Structure, and Subcreation. New York: Routledge, 2021.

64. Zaidi, Leah. "Building Brave New Worlds." Ontario College of Art and Design, 2017.

65. Zalace, Jacqueline. "How Big Is A Minecraft World?" The Gamer, 2024. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.thegamer.com/minecraft-world-size-area-volume/.

66. Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, 1989.

(Franklin, Ursula. The Real World of Technology. Toronto: House of Anansi, 2004. P. 12)

(Latour, Bruno. “Where are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, edited by Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law, 225-258. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.)

(Goldberg, Harold. "How The West Was Digitized: The Making Of Rockstar Games’ Red Dead Redemption 2." Vulture, 2018. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/the-making-of-rockstar-games-red-dead-redemption-2.html.)

(McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis H. Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. P. 6)

In an interview, “Red Dead Redemption 2” creator Dan Houser made the comment “...games are still magical. It’s like they’re made by elves. You turn on the screen and it’s just this world that exists on TV.” (White, Sam. "Red Dead Redemption 2: The Inside Story Of The Most Lifelike Video Game Ever." GQ, 2018. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/red-dead-redemption-2-interview.) This comment fueled a controversy persisting throughout the game’s launch about “crunch”, a game industry term that connotes long working hours often leading to employee burn-out. In consideration of this game’s relationship to crunch, audiences may perceive different qualities of the gameworld that otherwise generate different levels of coherence. Take for example the description of the “Cattleman Revolver” accessed in-game: “It is made by skilled laborers who work tireless hours each week and on the weekends for little pay in order to bring you the finest revolver in the field today. (Sarkar, Samit. "Does Red Dead Redemption 2 Contain a Hidden Reference to Developers’ Crunch?" Polygon, October 29, 2018. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.polygon.com/2018/10/29/18039824/red-dead-redemption-2-crunch-overtime-rockstar-games.)

(Culkin, J.M. “A Schoolman’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan.” Saturday Review, March 18, 1967, 51-53.)

8 (McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis H. Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. P. 55)

9 (Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books, 1988. P. 6)

(Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. The Routledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds. New York: Routledge, 2018. P. 82)

(Ibid. P. 90)

(Michel, Lincoln. "Against Worldbuilding." Electric Literature, 2017. Accessed September 5, 2021. https://electricliterature.com/against-worldbuilding/.)

(Ellis, Warren. “M John Harrison On Worldbuilding.” 2007. Accessed November 9, 2023. http://www.warrenellis.com/?p=4136.)

(Newitz, Annalee. "William Gibson On The Apocalypse, America, and The Peripheral’s Ending." Gizmodo, 2014. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://gizmodo.com/william-gibson-on-the-apocalypse-america-and-the-peri-1656659382.)

(Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. P. 1)

(O’Connor, Alice. "Physically Interactive Fiction: With Those We Love Alive." Rock Paper Shotgun, 2014. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/drawing-violences-mundanity-with-those-we-love-alive.)

(Consalvo, Mia. Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.)

(Sheff, David. Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. New York: Random House, 1993.)

(Nintendo. "Nintendo Power." Issue 1, July/August 1988. P. 62-69)

(Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950.)

(Gaboury, Jacob. Image Objects: An Archaeology of Computer Graphics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021. P. 12)

RenderMan was developed in-house at Pixar, introduced in 1988 by graphics pioneer Edwin Catmull who worked with a team of computer scientists, adapting it from a previous 3D CGI called REYES, an acronym for Render Everything You

(Price, David. The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Vintage, 2009. P. 95)

(Walker, John. "Wot I Think: The Vanishing of Ethan Carter." Rock Paper Shotgun, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/wot-i-think-the-vanishing-of-ethan-carter.)

(Reeves, Ben. "Afterwords – The Vanishing of Ethan Carter." Game Informer, 2014. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2014/10/24/afterwords-the-vanishing-of-ethan-carter.aspx.)

(Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. P. 71)

In systems engineering, top-down design is a development strategy where the system is viewed as a whole and subsequently divided into successive subsystems. Bottom-up design is an approach where individual components are designed first and then integrated to form interconnected systems. In worldbuilding, a top-down approach involves creating a high-level overview of the world in broad strokes. An example of this would be outlining geographic trends before articulating details such as cities then buildings then individual apartments for characters. This approach is useful for artists who want to build an integrated system to pull narratives from within. A bottom-up approach starts with specifying small details and extrapolating more complex systems from them. This approach is often taken by artists who begin with a story and use worldbuilding strategies to add complexity to it.

(Cheng, Ian. Emissaries Guide to Worlding. London: Serpentine Galleries, 2018. P. 59)

(Compton, Kate. “So You Want to Build a Generator.” 2016. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.tumblr.com/galaxykate0/139774965871/so-you-want-to-build-a-generator.)

(Compton, Kate. “So You Want to Build a Generator.” 2016. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.tumblr.com/galaxykate0/139774965871/so-you-want-to-build-a-generator.)

(Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. World-Builders on World-Building An Exploration of Subcreation. New York: Routledge, 2020. P. 225)

(Maiberg, Emanuel. “No Mans Sky’ Is like 18 Quintillion Bowls of Oatmeal." Vice, 2016. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.vice.com/en/article/nz7d8q/no-mans-sky-review.)

33 (Zalace, Jacqueline. "How Big Is A Minecraft World?" The Gamer, 2024. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.thegamer.com/minecraft-world-size-area-volume/.)

(Garrelts, Nate. Understanding Minecraft: Essays on Play, Community and Possibilities. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014. P. 179–181)

(Stephenson, Neal. Snow Crash. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. P. 37)

(Carlson, Kara. "At SXSW, Mark Zuckerberg Says Metaverse is ‘Holy Grail’ of Social Experience." Austin American-Statesman, 2022. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.statesman.com/story/business/2022/03/16/sxsw-facebooks-mark-zuckerberg-says-metaverse-future-internet/7051230001/.)

(Lepore, Jill. "Elon Musk is Building a Sci-Fi World, and the Rest of Us Are Trapped in It." New York Times, 2021. Accessed November 4, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/opinion/elon-musk-capitalism.html.)

38 (Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.)

This particularly struck me at a recent group exhibition I was in. For that exhibition, a fellow artist presented a linear digital animation that ended with a scene including a pastel-washed banner stating “Black Trans Lives Matter”. The collage of message, material, and aesthetics seemed so dissonant to me. I could not tell at the time why it struck me as being so discordant until I went to Target later that week. There I saw an in-store mural in almost the exact same visual style selling cleaning products. The dissonance was my experience of an unintended overlap on the artist’s part of countercultural politics and corporate advertising -all presenting themselves in the same ideological world. Adobe products made the aesthetic both visual artifacts shared incredibly easy to produce. For further analysis of this phenomenon, see: Troemel, Brad. "PASTEL HELL: The Definitive Guide to Millennial Aesthetics." YouTube, uploaded by Brad Troemel, November 25, 2020. Accessed May 22, 2024.

(Fisher, Mark. The Weird and the Eerie. London: Repeater Books, 2016. P. 58)

(Wolf, Mark J.P., ed. Exploring Imaginary Worlds: Essays on Media, Structure, and Subcreation. New York: Routledge, 2021. P. 191-224)

As a historical point of reference, I am interested in media archaeology currently being practiced in Linden Lab’s Metaverse platform Second Life that launched in 2013 and persists today. See: Bucknell, Alice. "Second Life’s Loyal Users Embrace Its Decaying Software and No-Fun Imperfections." Document Journal, 2024. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://www.documentjournal.com/2024/05/second-life-virtual-world-gamer-furry-identity-world/.

( Weisenburger, Kirsten. "Enter The Zone – Episode 1: How a Band of Pranksters Inadvertently Created Burning Man." Journal of Burning Man, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://journal.burningman.org/2021/08/black-rock-city/building-brc/zone-episode-1-how-pranksters-created-burning-man/.

(Morris, Holly. "The Stalkers." Slate, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/09/the-stalkers-inside-the-youth-subculture-that-explores-chernobyls-dead-zone.html.

(Shklovsky, Viktor. Theory of Prose. Translated by Benjamin Sher. Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1990.)

(Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and translated by John Willett. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964.)

(Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-Stories.” In The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, edited by Christopher Tolkien, 109–161. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1983. P. 145)

The exact quote is “It seems to be easier for us today to imagine the thoroughgoing deterioration of the earth and of nature than the breakdown of late capitalism; perhaps that is due to some weakness in our imaginations.” (Jameson, Fredric. The Seeds of Time. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. P. XII)