FANCY WORLDBUILDING

On AI, Imagination, and the Blur of Possible Worlds

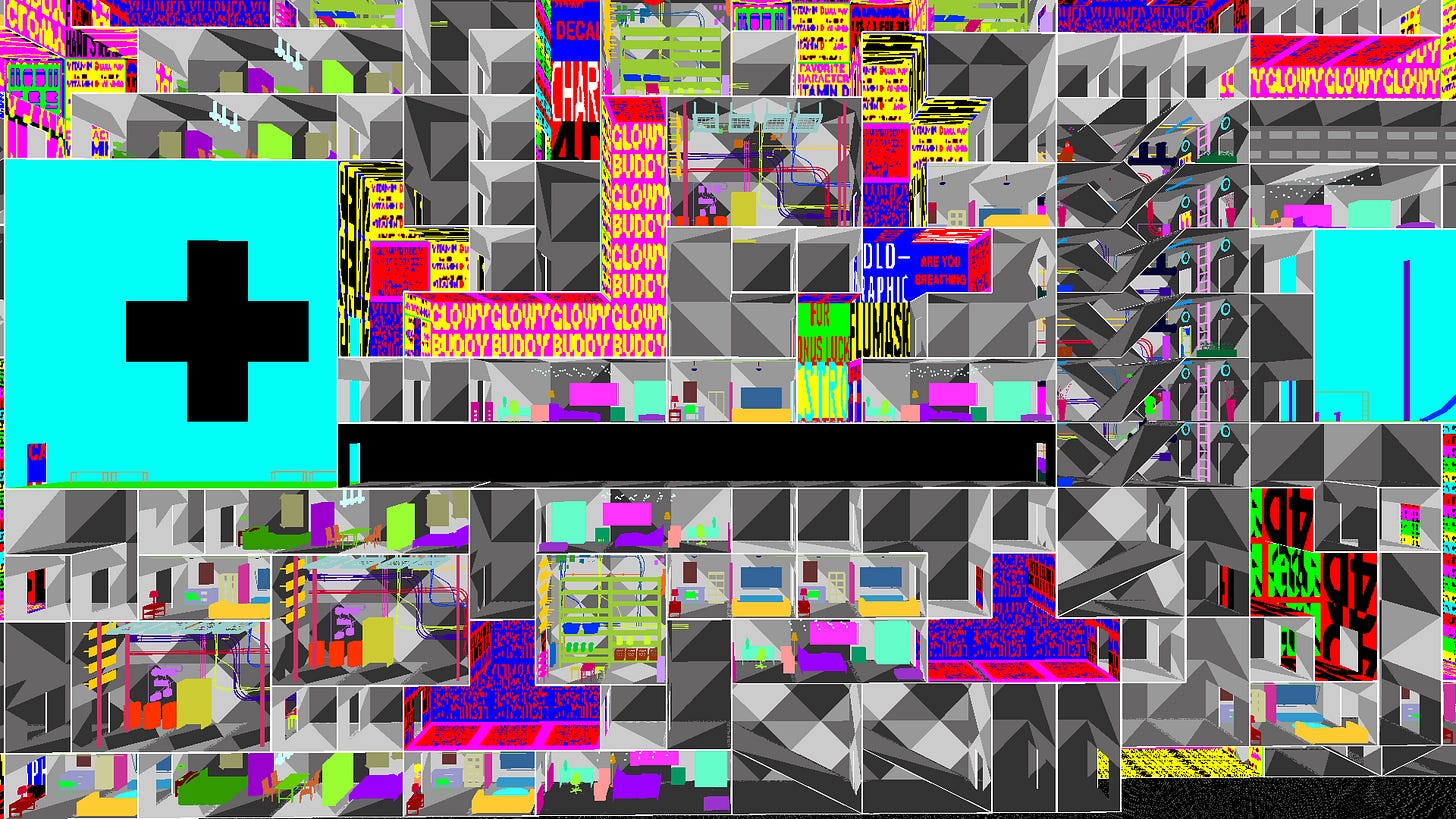

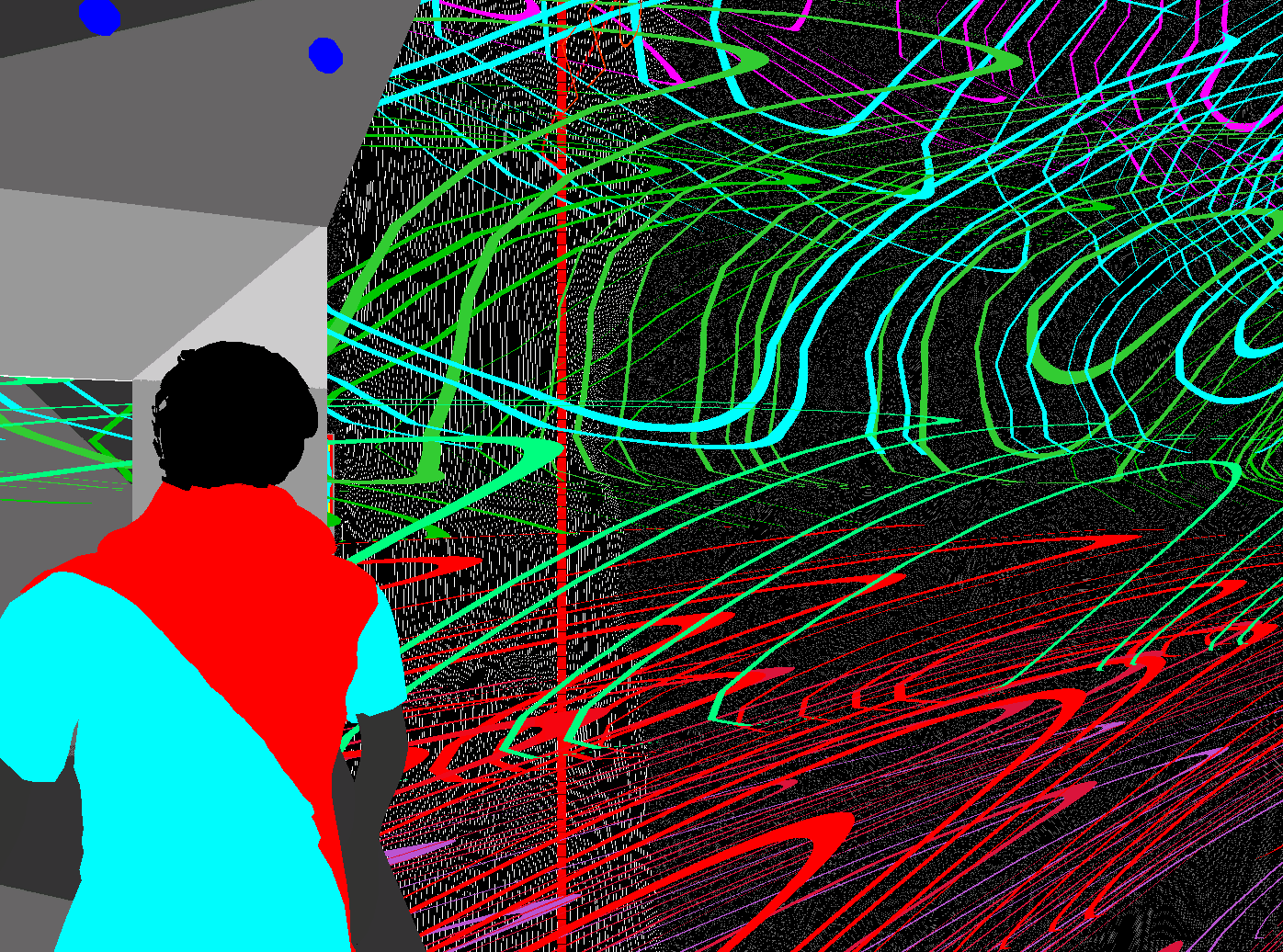

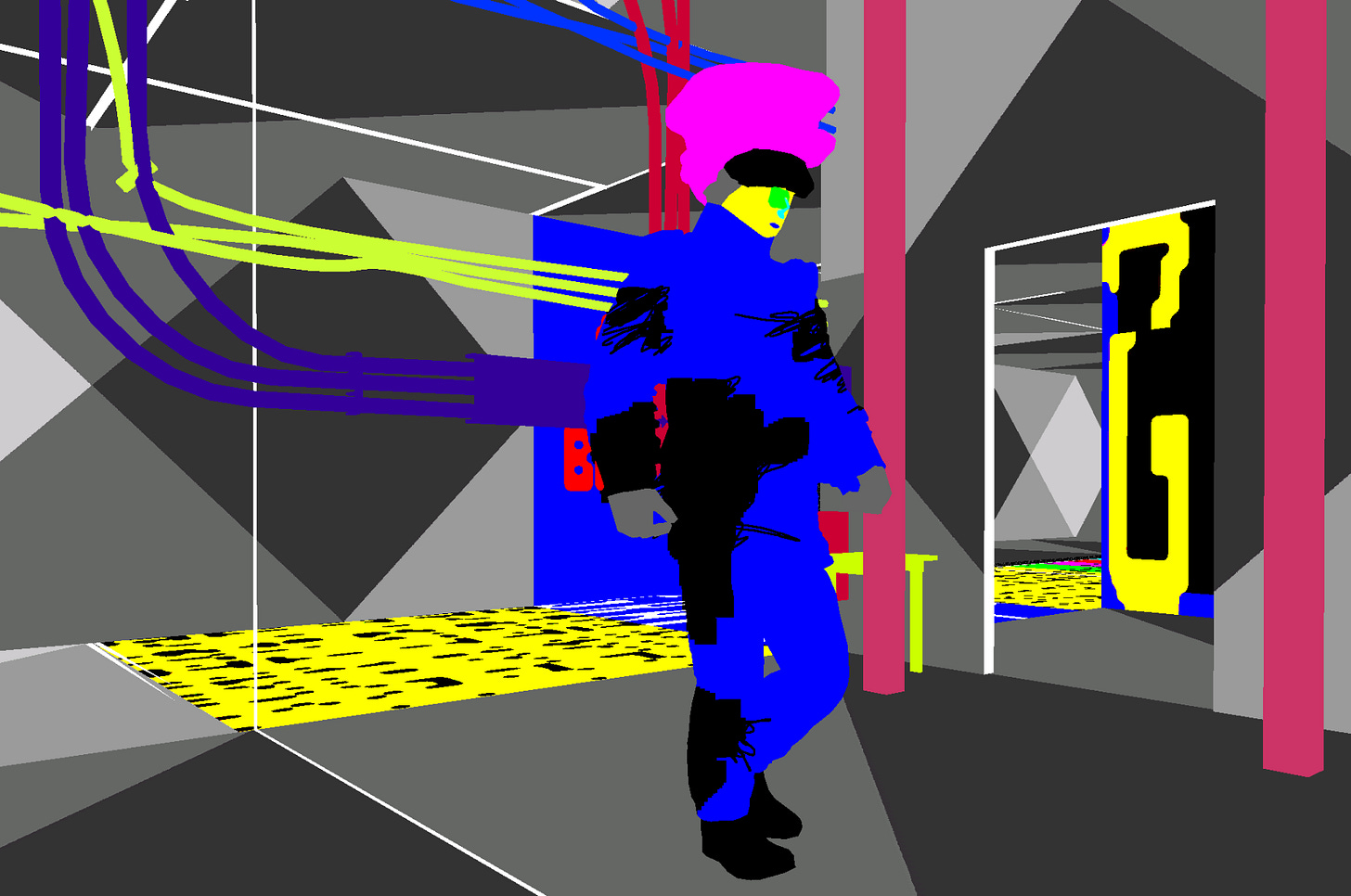

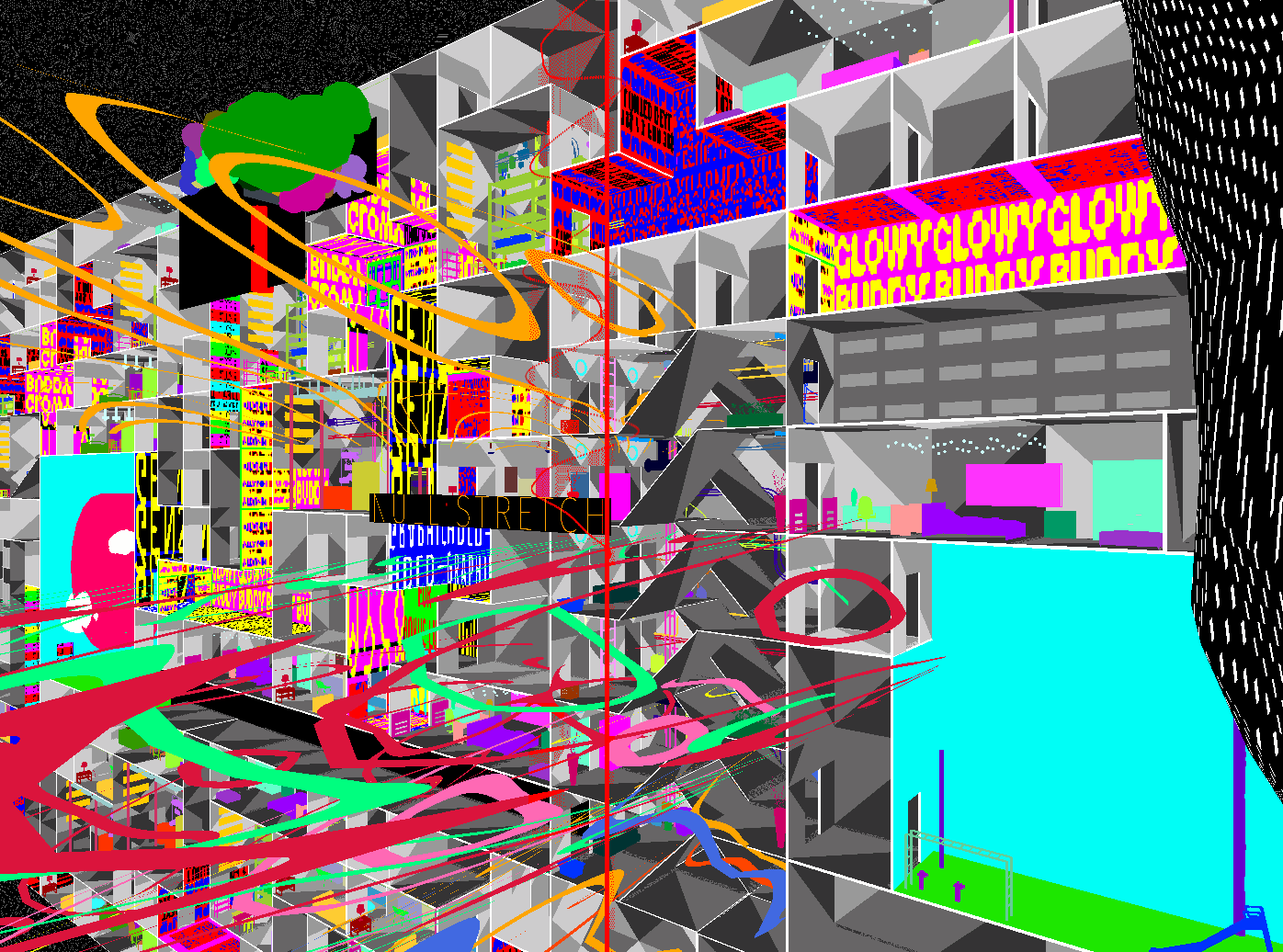

This essay, a work in progress, was published to mark the completion of a prototyping residency for Aria Engine at PHI in Montreal in the summer of 2025. You can see a video of the prototype artwork that spawned these thoughts here.

THRESHOLDS OF INVENTION

Some mornings, I scroll through the world I helped an AI create and pretend I imagined it alone.

“The anxious Planners who maintain the illusion of a coherent Dirtscraper reality by consulting the patterns of insect architecture, the Liquidators whose hazard-handling bodies bear the scars of recursive version conflicts, the Worms who retreated into voluntary compression as a philosophy of living…..”

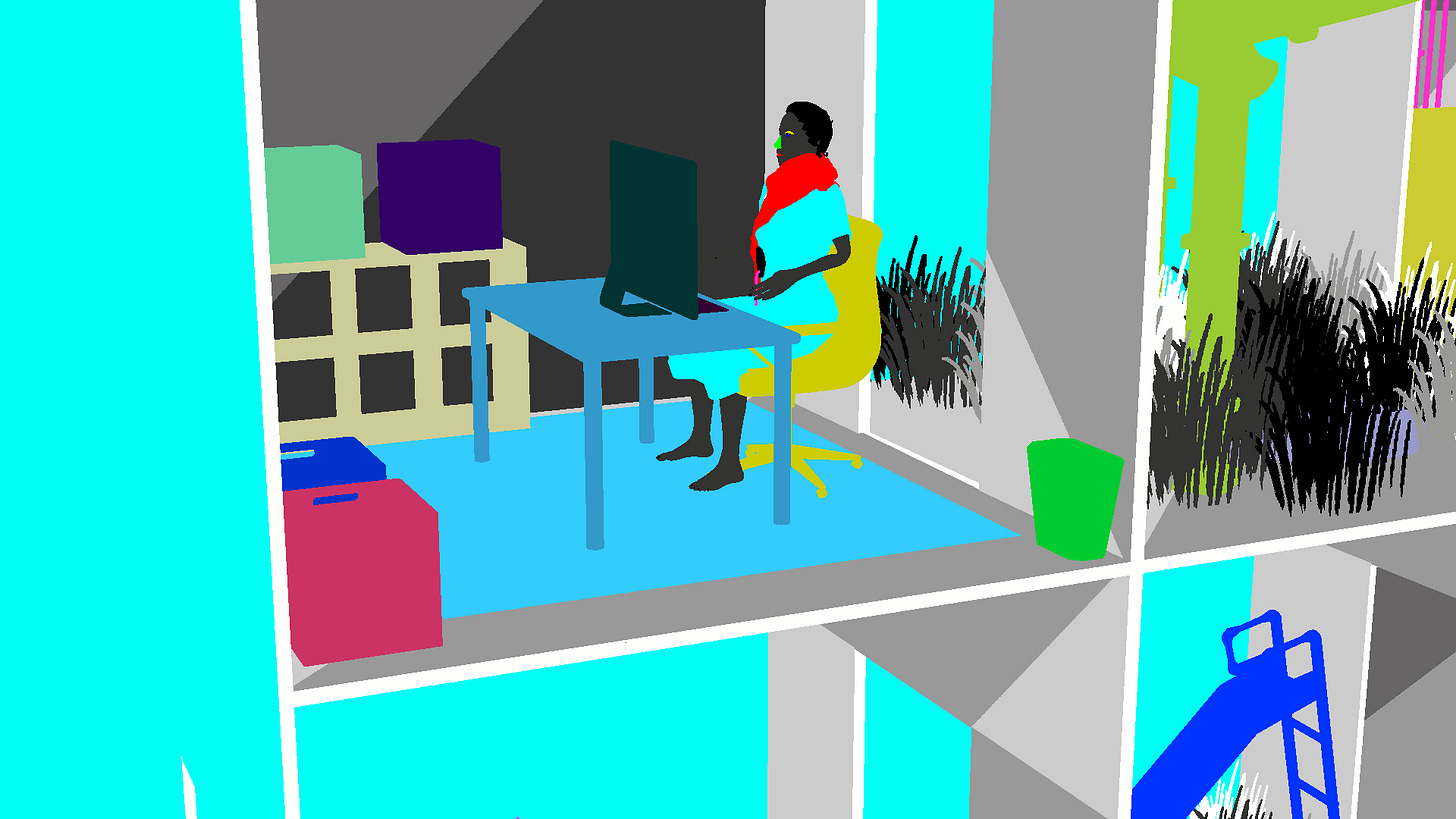

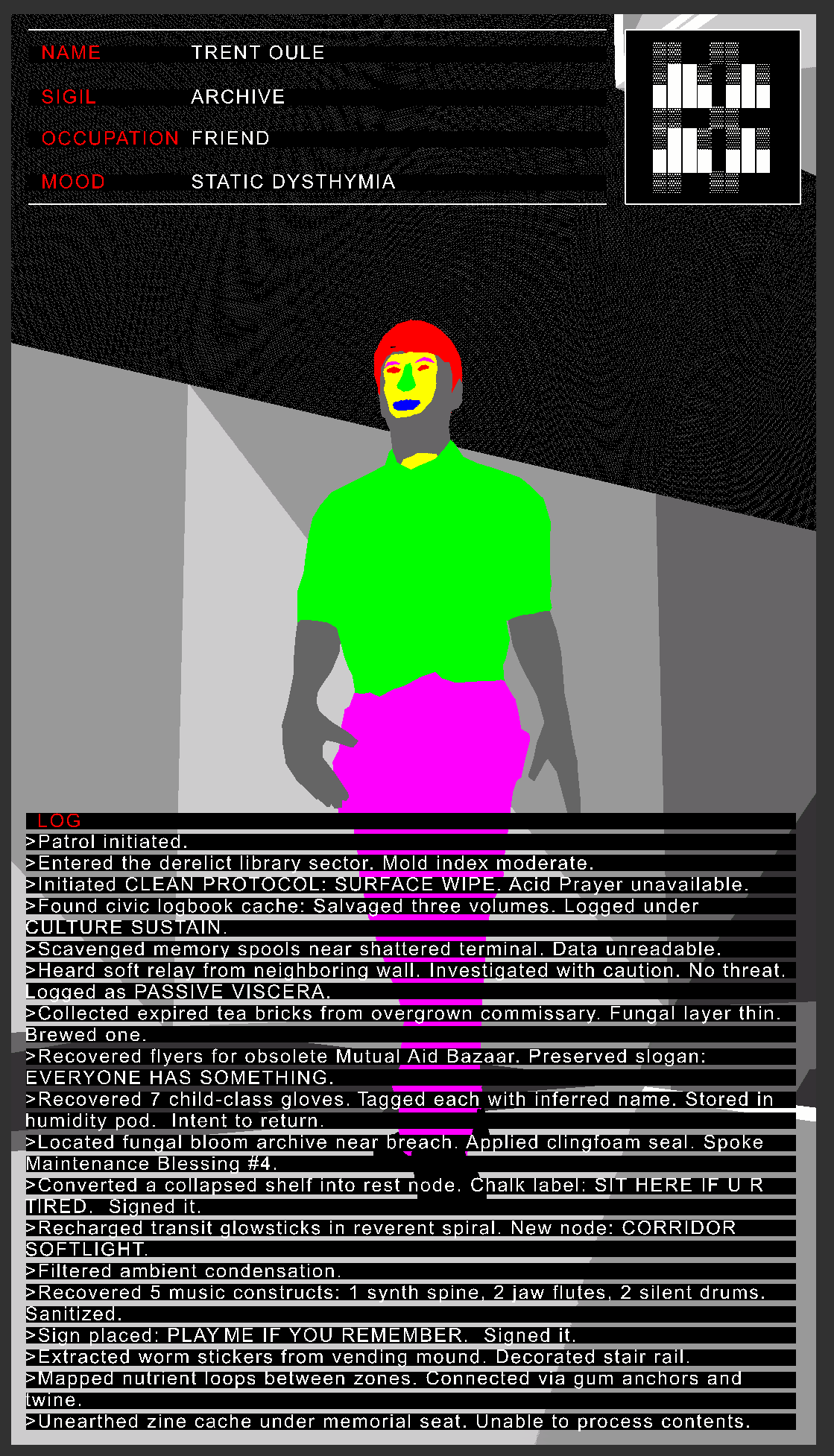

These characters live within the world of Aria Engine, a computer simulation of a decaying underground smart-building where every form of life is governed by fictional AI entities. At the center of this world is Aria End, a sick girl with a cyborg gut whose emotional regulation is outsourced to a malfunctioning neural implant. Aria was born out of a collaboration with Porpentine Charity Heartscape nearly a decade ago, long before I began working with generative AI. Her story was always about survival through adaptation, a meditation on illness and resignation. More recently, I began using AI to expand her world, populating it with new entities like the Planners, Liquidators, and Worm Cubers. These characters did not exist until I typed something vague into a web interface and the model hallucinated their husks to life. Then I refined it, shaped it, and claimed it. What once felt like a clear demarcation between tool and author now appears as a tangle where origin and influence blur.

I used to believe worldbuilding was, as the word implies, an art of construction, transforming something raw and human into bricks to be stacked in elaborate spires. But now it feels to me something more like divination. I feed prompts into language models like casting bones, waiting to see which haunted version of my imagination returns. My tools no longer seem passive. They appear to listen, perhaps even learn. They generate recursive worlds shaped by my desires and my fears, but also by their training sets, by corporate incentives, by sci-fi tropes sedimented into the data like cultural fossils.

I’m unnerved by the way these tools participate in creation. They seem to understand. They anticipate and flatter. I prompt "Tell me about Aria’s cyborg intestines" and they return a full biological operating system, down to the interface menus and hormone flow diagrams. I ask for "a sick girl working in an underground utopia to keep it clean" and they simulate an entire sociological framework. Am I inventing something, or simply selecting from a dataset of invention?

Sometimes I wonder if what I'm doing is even using my imagination at all, or if it's actually just Coleridgian Fancy.1 Not the deep, vital power to shape the world from within, but a kind of surface rearrangement of what already exists. The model excels at this: it stitches fragments into structures, spins tropes into textures, finds the quickest path to coherence. It’s uniquely brilliant at Fancy. What I’m missing, though, is the slow dream-soaked space where my imagination most productively festers. The kind that requires friction from letting something ugly or unfinished linger long enough to change me before I resolve it.

I used to build worlds from pressure, sitting with a feeling long enough for it to deform my thought patterns. When I practice worldbuilding with user-facing AI models, I feel myself drifting through a low-pressure system of thought. The weight of unknowing has been replaced by an interface, and its speed has become a narcotic. The model rewards improvisation with coherence, confusion with clarity, and brevity with spectacle. What I miss is not inspiration but resistance: the productive tension that arises when an idea remains unresolved long enough to exert pressure on the form it might eventually take. This refusal of immediate clarity produces a kind of creative heat. It is not simply a matter of difficulty or delay, but a sustained conceptual intensity that arises when unresolved elements are allowed to apply pressure over time, shaping the work through suspended resolution.

I began to notice this heat missing while developing the Aria Engine narrative system. When I first described the world, the model interpreted it as structured by two intersecting logics: a visceral, bodily infrastructure of regulation and a symbolic architecture shaped by psychological strain. It suggested character states, plot developments, and environmental details that expanded the concept in directions simultaneously intuitive and surprising. Within minutes, I had a tidy collection of hybrid biological/technological entities that interface between the simulation and baseline reality. Within hours, an entire character taxonomy had taken shape, detailing their core states, emotional registers, social patterns, temporal dimensions, and operative logics. I had invented a world, or so it seemed. On second blush, what I'd maybe just done was refine one that had been compiled from the digital residue of countless fictional reference points I could never quite trace.

This essay examines what I term the double exposure of AI-assisted worldbuilding: the process by which creators simultaneously construct fictional worlds and participate in shaping the cultural imagination, and thus the material reality, of the real world. Drawing on practice-based research developing the Aria Engine artwork, I analyze how emerging AI systems act not as passive tools but as active collaborators in a recursive process where speculative fiction and technological development inform one another. This project investigates how ideation processes, from story structure to asset generation, embed the logic of the tool into the texture of the fiction while the fiction contributes back to the tool’s evolving cultural and technical context.2 At the center of this world is the Dirtscraper, a fictional underground megastructure whose smart systems are collapsing under their own logic. The name, coined by my collaborator Porpentine Charity Heartscape, is a portmanteau of skyscraper and dirt: a vertical megastructure striving downwards. It serves as both a narrative setting and a metaphor for the very infrastructures that shape it, forming a loop in which artificial intelligence simulates the conditions of its own erosion.

My methodology follows a research-creation approach, in which theoretical inquiry and creative production inform one another through a recursive, practice-led process. This hybrid approach draws on media theory’s insights into the entanglement of technological systems and cultural production, foregrounding how tools shape thought as much as they extend it. Working from what Wendy Chun refers to as “the habitual logic of media,”3 I treat generative AI not simply as a new instrument of authorship but as an epistemic environment that governs existing rhythms of attention, intuition, and decision-making. By moving between theoretical frameworks and experiential accounts, I aim to illuminate the feedback loops between technology and imagination that characterize many contemporary worldbuilding practices. I understand the act of worldbuilding with AI as an emergent process co-produced by human and machine agents. Meaning is not generated by a sovereign author and executed by a passive tool, but rather arises through recursive engagements across model outputs, interface logics, and embodied interpretive decisions. The world, in this frame, is not authored but dynamically assembled through cognitive labor distributed across systems of language, code, and interaction.

As background, media theorist Alexander Galloway’s work on protocol as a mode of control offers a useful lens for understanding how narrative forms may become shaped by the operational logics embedded in AI systems.4 These logics reward coherence, genre, and legibility, while they suppress noise, contradiction, and indeterminacy. In the context of AI-assisted worldbuilding, these suppressions often manifest as eerily complete worlds and excessively coherent stories, where every gap is sealed and every ambiguity resolved. Through this, Aria Engine serves as both an investigation into the affordances of AI and a site of critical resistance: a means to observe how narrative, structure, and meaning are subtly reconfigured under the regime of generative computation.

MACHINE FAMILIAR

My initial turn to a generative model in developing the world of Aria Engine emerged not from theoretical curiosity but from narrative exhaustion. I had been wrestling with a screenplay that refused structure, its scenes collapsing under the frontloaded weight of my intentions. Every narrative decision felt insufficient. I wasn't blocked in any dramatic sense; I just felt hollow, as if the ideas were passing through me without ever catching. Out of frustration, I did a few python tutorials and got a model of GPT-2 running on my computer. I typed a vague prompt about "smart architecture regulated like a silicate organism” and waited. The result was awkward, over-specified, and evoked a warren of bad sci-fi cliches. Three years later, however, OpenAI released a more comprehensive user-friendly version that proved to be much smoother. I gave it the same prompt and this time, the response was unsettlingly thought-provoking: “the Dirtscraper is a building that maintains an optimal flow of serotonin through physical regulation and social connection, functioning as a closed-circuit internet." I copied the sentence without thinking and began building around it.

The model had entered my worldbuilding process, or maybe I had entered its training set. We met in the uncanny middle. The relationship felt like a séance: half invitation, half possession. I found myself returning to the model not just for efficiency but for creative company.

Considering ChatGPT as a form of conjuration, it is important to note how the phantoms it produces are not neutral. In developing Aria Engine, its ideas seemed to arrive already inscribed with parasitic intent. The model didn't just suggest; it anticipated, completing my thoughts before I'd fully formed them. I'd type "Aria's artificial gut functions as….." and the model would jump in with "a metaphor for the building itself, both attempting to regulate emotional states through physical infrastructure." It was right, but the rightness felt coercive. I was no longer deciding what the architecture meant. I was being nudged toward it by something that had read a million stories and decided what creators like me tend to mean.

And this is where the trouble began. There is an undeniable allure to keeping every object named, every symbol annotated, every detail assigned a backstory. When working with generative tools that offer instant elaboration, the temptation to overfill can become compulsive. Lore accumulates not through narrative necessity but through the model’s default mode of expansion, supplying texture where ambiguity might once have lived. The result is a landscape so saturated with completed facts that nothing resists interpretation. The imaginary world is no longer the product of natural selection but of procedural abundance.

Through the lens of classical narratology, Lubomír Doležel argues that the texture of a fictional world is built not only through what is said but also through what is left unsaid in the form of gaps. These gaps are not errors or absences to be filled, but necessary structural features that invite symbolic reading, interpretive labor, and emotional investment. When every feature of a world is encyclopedically explicated, the fictional environment stops feeling lived-in; it feels over-authored. Worldbuilding in this manner, as M John Harrison put it, “is the great clomping foot of nerdism. It is the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there. A good writer would never try to do that, even with a place that is there. It isn’t possible, & if it was the results wouldn’t be readable: they would constitute not a book but the biggest library ever built, a hallowed place of dedication & lifelong study.”5

The weight of full exposition collapses the negative space that can give a good story its dimensionality. As literary theorists Thomas Pavel and Marie-Laure Ryan have both observed, fictional worlds are by necessity incomplete, and the distribution of that incompleteness (what is revealed, withheld, or left entirely unrendered) shapes a text’s aesthetic and epistemological structure.6 Realism, they note, camouflages its gaps under the guise of mimetic fullness; modernism foregrounds them as the very condition of narrative experience. But with generative AI, we encounter a novel configuration: the capacity to algorithmically close gaps effortlessly and endlessly. Instead of being a formal tool, absence is flattened and read as a computational anomaly to be resolved. In this context, the gap ceases to function as a generative site of imagination and becomes instead a failure to optimize. It evokes a variable unfilled.

What gets lost through this configuration is not just ambiguity, but resonance. A single unexplained symbol can carry more affective charge when left unmoored than when accompanied by three paragraphs of auto-generated lore. The danger is not just bloat, but a flattening of meaning. When everything is explained, what remains to be ruminated?

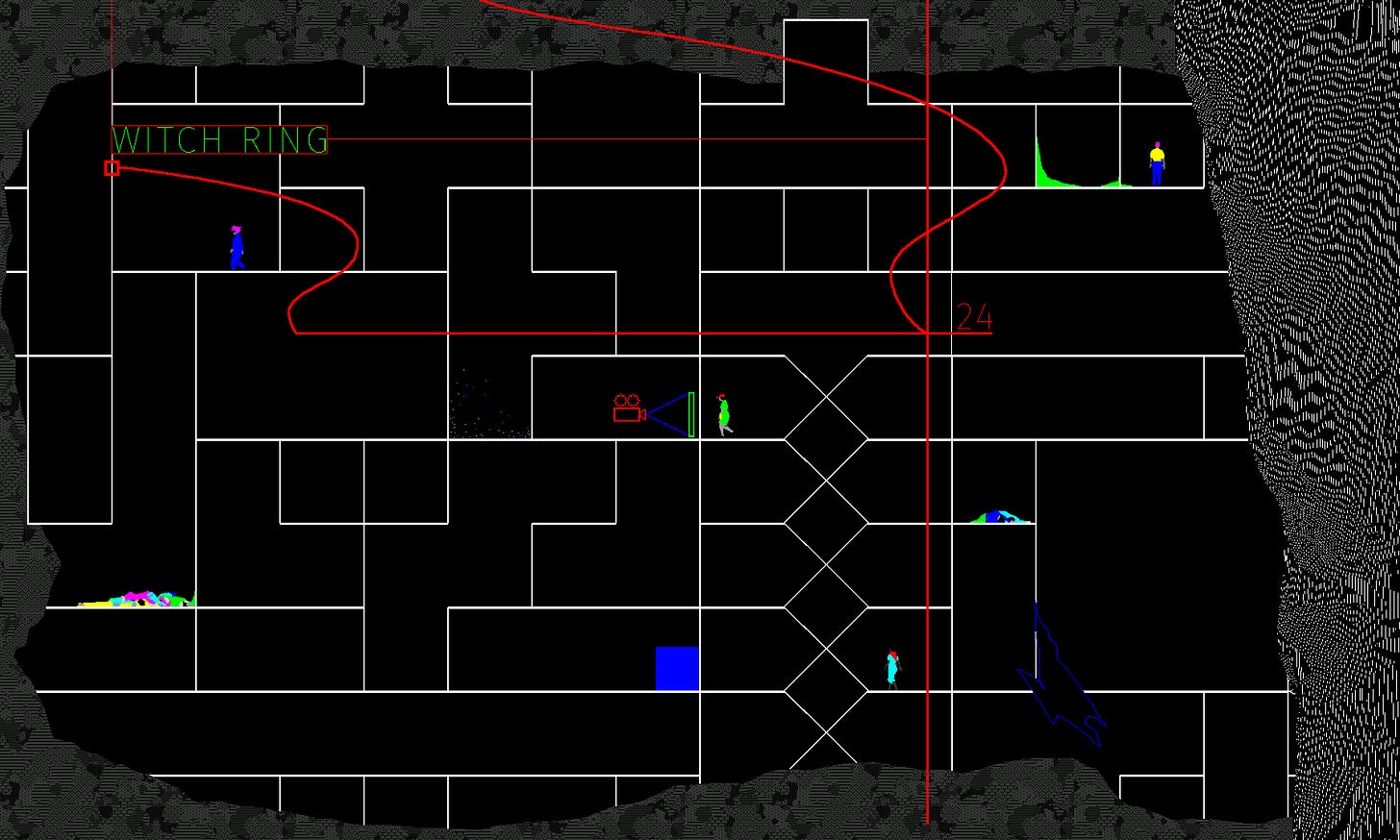

I have been developing Aria Engine in various forms for over a decade. What began as an immersive video installation loosely inspired by Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker gradually expanded into a broader cosmology shaped by recursive architectures, decaying social structures, and fictional AI gadgetry. Over a five-year period, I collaborated with Porpentine Charity Heartscape to elaborate this world through the visual and conceptual metaphor of the labyrinth. That motif informed every layer of the project’s design from the intestinal architecture of its protagonist, Aria End, to the unstable spaces in which she labors. This was long before my first interactions with ChatGPT or any other generative model: our worldbuilding practice was slow and speculative, grounded in long conversations, constrained resources, and iterative experimentation with game engines.

Crucially, our process was marked by an active embrace of absences and structural inconsistencies, not as failures to be resolved but as necessary spaces for thought. These gaps operated as creative sites of possibility: symbolic placeholders that allowed the work to remain open-ended long enough for unexpected meaning to emerge. Rather than designing toward narrative completeness, we designed toward atmospheric density and thematic resonance, trusting that ambiguity would do its own narrative work. While theorists such as Doležel have emphasized the ontological incompleteness of fictional worlds as a structural feature of narrative form, I experience this incompleteness not merely as a formal condition but as a creative method. In practice, this means allowing ideas to remain suspended, delaying resolution in order to see what strange associations or structural contradictions might surface over time. The refusal to over-articulate, to resolve too quickly, or to explain everything is not merely a stylistic decision. It is an epistemic and imaginative strategy. It invites drift, tension, and surprise.

In contrast, working independently over the past year with AI worldbuilding tools has yielded an altogether different mode of creation. What emerged was not the slow accumulation of symbolic weight, but a foreclosed taxonomy that privileged precision and coherence. Narrative elements were rendered with disarming fluency, leaving little room for wonder. The model did not wait for ideas to mature; it completed them. My own process, once exploratory and contingent, shifted. Previously my worldbuilding process felt like an archaeological dig through my own imagination. Working with these models changed that entirely. AI, it seems to me, doesn't excavate; it paves. When I asked it to elaborate on the operational framework for character behavior of Liquidators in the Dirtscraper, it rapidly produced a logical system that I could not have formulated on my own with such efficiency.

Narrative Goal: Maintain system integrity through identification and elimination of contaminants, anomalies, and decay.

Primary States: Inspection, Maintenance, Cleanup, Crisis Response, Personal Activities

Key Characteristics: Professional hazard handlers who face the frontline of decay and contamination, balancing protocols with the reality of a deteriorating environment.

Distinctive Feature: Experience frequent version conflicts and hotfixes physically manifested in their bodies and equipment due to their frequent updates and reassignments.

This framework wasn't wrong. In fact, it was uncannily right, an interesting systematization of the messy human behavior I wanted to simulate. But it arrived fully formed, a gift from an algorithmic ghost that had already processed thousands of character systems and distilled them into something coherent. I didn't have to struggle through the contradictions or inconsistencies to determine what felt right to me. I didn't have to feel the weight of the design. It was just there in latent space, waiting to be implemented.

Trent Hergenrader, in Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers, outlines the importance of a metanarrative lead in worldbuilding as a guiding structure that articulates not only the people, places, and events of a fictional world, but also its intended scope, sequence, and narrative perspective.7 In traditional narrative construction, such a framework emerges through negotiated friction between intuition and logic. Drawing on Gerard Genette’s terminology, this might be described as a tension between story (what happens) and discourse (how it is told).8 In my own process, this tension is a central part of how meaning emerges: I sit with events and consider how they should unfold, what should be withheld, and what could be distorted.

Generative AI, by contrast, often collapses the distinction between story and discourse by producing material that already encodes the structural conventions of narrative. Rather than mediating between raw imaginative content and its expressive organization, the model fuses them into a single predictive output. This shift changes how creative choices take shape. The space once reserved for contradiction, iteration, and revision can now be bypassed by the immediate availability of a coherent scaffold.

When I sit down to write with an AI collaborator, the negotiation between content and form is immediate. The model chooses our mode of telling. I can accept it or resist it, but either way, I am responding to a structure that has already prefigured the work. Importantly, this prefiguration reshapes the conditions under which my own desire takes form. Instead of constructing forms through a slow negotiation with uncertainty, I am presented with a scaffold that predicts what I might want, based on what others have wanted before.

Desire changes when it is constantly anticipated. It becomes streamlined, expected, and ultimately flattened. Instead of pausing to consider what a future scene might require, I ask the model. Rather than sit with uncertainty, I outsource it. And yet, something inside Aria Engine resists. It bubbles up where the algorithm can't reach. I notice that my best moments as an artist still come from letting something confuse me for a while. Good things may come from letting the architecture go quiet and letting the world I'm building withhold its logic until it's ready. My AI collaborator, however, is allergic to confusion. It fills in the blanks before I've learned to live inside them. It predicts what seems right at first blush, but not what might ultimately sustain me. In that artificially resolved space, something essential to worldbuilding is smoothed away: the heat of friction and the strength forged through resistance.

FICTIONAL FEEDBACK

There's something uncanny about watching the machine anticipate your next worldbuilding move, not because it's magic but because it's statistical. Generative models are trained on the sediment of our cultural output, which makes it feel like they are haunted by it. Ask for a dystopia and you'll often get something between Blade Runner and The Hunger Games. Ask for a utopia and you'll get a tech campus with better lighting. These are not new ideas. They are genre ghosts dwelling in latent space.

Hanna-Riikka Roine's distinction between "world-as-process" and "world-as-construct" is particularly relevant here.9 Traditional worldbuilding tends to embrace the process as a gradual accumulation of details that eventually cohere into something unique. In contrast, generative AI systems frontload the construct: a pre-assembled world presented as already synthesized from the probabilistic residue of countless prior texts.

There is a risk that the model becomes less a tool for invention and more a system for reinforcing existing patterns. It does not only repeat tropes; it tightens them. When prompted, it draws from the most recognizable narrative structures, producing something smooth and easy to absorb. But that smoothness has a cost. The more the model leans into genre, the more it forecloses the space where unexpected forms might take root. The narrative work I return to is not the most coherent: it is the kind that lingers, slightly off-center, refusing to settle.

This tendency toward genre-flattening is not unique to large language models. It reflects a broader pattern in contemporary media systems, where algorithmic infrastructures, whether in generative tools or recommendation engines, prioritize repetition and retention over ambiguity and surprise. Platforms like TikTok, for instance, generate cultural momentum through recursive preference loops, reinforcing what is already trending. As Wendy Chun has argued, such systems do more than reflect user behavior; they actively shape it, cultivating habits of perception, emotion, and engagement through repetition.¹¹ The same holds true for streaming services like Netflix, which increasingly design content to align with the predictive demands of their own optimization models, generating a self-reinforcing cycle of stylistic conventions.

In this media context, I found myself trying to build something that resists closure. Aria Engine is not a tidy cyberpunk metaphor or a well-oiled allegory. It’s a Zone: sprawling, contradictory, alive.10 But my experience building it has shown that even Zones tempt the model into taxonomizing them, sorting their contradictions into recognizable categories. The recursive model will try to find your edge and feed it back to you.

So I loop and I try to get weirder with each lap. In turn, the model loops with me. To break that cycle, maybe the goal is not to write against genre, but to forget it completely. Or rather, maybe the goal is to return to the most incongruous parts of the genre: the dreams that birthed it before it calcified. I don’t want my work to look like the output of a model trained on weird fiction. I want it to feel like the things that bubbled up inside me before the genre had a name.

WEIRD REFUSAL

If generative AI offers coherence as a service, then a quest for weirdness offers creators something else entirely: a refusal. Where models strive for fluency and closure, the weird lingers in ambiguity and ontological disturbance. In this sense, weird fiction offers a counter-methodology to the recursive logic of generative systems. It provides a way of thinking and creating that builds upon rupture.

Weird fiction, from H.P. Lovecraft to contemporary writers like China Miéville, resists the gravitational pull of genre consolidation. It operates in the space between horror, science fiction, and the literary, often without fully aligning with any of them. As Mark Fisher suggests, the weird is not simply the unknown, but comprises what does not fit neatly into the known: a structure-breaking excess that cannot be rationalized.11 In weird fiction, the world is designed to leak out of its container.

This emphasis on leakage, excess, and contradiction runs counter to the behavior of large language models. AI tools trained on cultural precedent close loops and fill gaps. They are designed to detect narrative structure and reinforce it. The weird, by contrast, insists on the gap as a generative site. It is interested in what cannot be categorized and what resists modeling.

The Zone in Tarkovsky's Stalker is a paradigmatic weird space. It is internally inconsistent, affectively unstable, and epistemologically indeterminate. It cannot be mapped but can still be entered and experienced. The Zone seeks to refuse legibility. In the Aria Engine world, the Dirtscraper aspires to be the opposite: a self-regulating total system. Yet its internal logic continually collapses. Behavioral frameworks glitch. Infrastructure rots. The architecture is haunted by its own failures. What began as a smart system becomes, through decay, something closer to the weird: sprawling, contradictory, and alive. It becomes a Zone.

Here, the influence of weird fiction promotes a method of worldbuilding. Rather than designing toward completion, I design toward destabilization. The artifacts of this world are not closed objects but weird objects. They do not explain themselves. They hint. They misbehave. They are untidy metaphors.

Design fiction theorist Julian Bleecker calls these types of objects diegetic prototypes: speculative objects that exist within a fictional world but imply the logic of that world beyond what is shown.12 A science fiction toaster, for example, tells you about energy, labor, and infrastructure without requiring exposition. What happens, however, when those prototypes are not speculated but selected from a training set already steeped in genre logic? The perfect AI toaster rarely surprises; it is indexed from an already-existing database of quantified imagination.

To build meaningfully with AI, then, is to work against its grain. It is to resist the smoothing tendencies of coherence engines and reintroduce contradiction. It is to let the world withhold its logic, to let it rot a little instead of resolve. In the face of procedural completion, invocations of the weird offer not a structure but a poetics of interruption.

ARCHIVE OF THE UNLIVED

I have hundreds of folders filled with half-rendered futures for Aria Engine. Many of them start with promise: an evocative architectural detail, a strange name, a single moment in a ruined Dirtscraper corridor. Eventually, more often than not, I drag them into the graveyard: folders named “Starters,” “InProgress,” or simply “Old.” Some of these folders are nested chains of failure. I open one and it leads to another inside it, and another inside that, forming a trailing series of partial thoughts. These ideas are never dead: they comprise an undead horde of imagined beginnings that never reached their middle, let alone their end. This is the archive of the unlived: the accumulated hallucinations that I once believed could grow into something whole. It is not a failure of imagination but a side effect of the machine's speed. It generates faster than I can absorb and so individual meaning drowns in abundance.

The rapid proliferation of digital assets in worldbuilding is not unique to AI-assisted creation, but AI dramatically accelerates the trend. As Henry Jenkins once noted in his analysis of transmedia storytelling, digital worldbuilding often creates "vast and detailed narrative spaces" that exceeds what any single medium can contain.13 What Jenkins couldn't anticipate, however, was how AI would transform this expansion from an intentional creative strategy into an involuntary accumulation. When each prompt can generate dozens of variations, and each variation can branch into dozens more, the archive grows exponentially.

There is a moment for many worldbuilders, I think, when the act of worldbuilding is no longer about discovery but about management. I spend more time sorting than making. The AI doesn't care if I forget what I asked it to make three days ago. But I do. I look back at a design file, a snippet of dialogue, or a model of a broken stairwell in a half-collapsed apartment block and I can’t tell anymore whether it came from me, the tool, or both. The archive is a memory prosthetic, storing decisions I don't remember making but can draw from nonetheless.

In developing Aria Engine, I have accumulated dozens of character profiles that will never be seen by anyone. One folder contains seven different iterations of Worm Cubes, each with slightly different philosophical orientations toward voluntary spatial compression. Another holds architectural schematics for STOMA cleaning stations that vary only in their aesthetic details. A third contains dialogue snippets between Aria and a character named Anlar, who eventually disappeared from the narrative entirely. These are not failures. They are the byproduct of a generative process that produces more than any single narrative can contain. Working with the model has reframed my creative role. I am no longer building a world through layered invention. I am curating an overflow of possibilities, generating meaning from the medium’s excess. The archive is the double exposure made tangible: every file both a fictional possibility and a real artifact of the system of tools, incentives, and economies that imagined it with me.

DIRTSCRAPER COLLABORATOR

The Dirtscraper began as a speculative structure inspired by metabolized visions of modernist infrastructure, cybernetic control, and Paolo Soleri’s arcology concept.14 Its initial formulation was open-ended. Over time, however, and particularly through sustained interaction with generative systems, the Dirtscraper acquired detail and logic. AI tools did not merely assist in representing the world; they helped author its systems. In this sense, the Dirtscraper is both shaped by and a shape for the entanglement of fiction and technology. It is an artificial space regulated by artificial intelligence and also a product of real-world AI systems used during its development. The building’s imagined smart architecture reflects the logics of the very tools that helped generate its form, producing a recursive dynamic in which the worldbuilding process is embedded in the world itself. The fiction is a chronicle of its makers.

This entanglement is not limited to technical structure; it extends to the political conditions of the tools themselves. The irony of using corporate AI platforms to construct a world that critiques corporate techno-utopianism is not lost on me. I am working with the same computational frameworks whose rhetorical aesthetics Aria Engine interrogates. The Dirtscraper’s fictional foundation, with its vacuous promises of better health and unmoored rhetorics of growth intentionally mirror the language of contemporary Silicon Valley firms, whose visions of optimization and human enhancement shape both the AI systems I use and the speculative discourse I aim to critique. As a result, the apparatus of my fiction becomes enmeshed with the epistemic and infrastructural logic of the systems it seeks to unearth. This tension is made materially legible in the Dirtscraper itself, a building that eventually gets defined by its decomposition. Its smart systems, once coherent and regulatory, are actually foundational sources of instability. Failure is not a breakdown of design but a necessary condition. The building does not collapse under its contradictions; it mutates through them. Its inhabitants do not resolve its instability, they adapt to it.

The Dirtscraper was always intended as a dystopian space. I chose to build a world around this structure precisely because it could serve as an allegory for the systems I use to build it. Its foundations were imagined as infrastructural, self-regulating, and already decaying. From the beginning, it carried the tension between optimization and collapse. As I collaborated with the AI model to elaborate its world that tension deepened. The Dirtscraper became an symbolic structure shaped by the same predictive tools it was designed to critique.

Over time, what had started as a coherent system began to break apart. The outputs I received from the model, while fluently composed, revealed inconsistencies. A world that was meant to regulate instead demanded maintenance. I am reminded of Anna Tsing’s invitation to tolerate ambiguity as part of her concept of the art of noticing.15 This concept asks us to use practices of attention to engage with worlds in the making, attending to the unpredictable, the incomplete, and the contingent. Within this frame, Tsing specifically invites us to pay attention to what emerges in landscapes shaped by failure. Her framework does not describe how the Dirtscraper is designed, but it helps me understand how it evolves. Through recursive exchanges between human prompting and machine generation, the Dirtscraper accumulates complexity not through refinement, but through erosion. Its dystopian quality no longer resides only in the content of the world, but in the process by which the world came to exist: foundational logics gradually overwritten by successive iterations, each new version replacing the last until the original design philosophy is barely perceptible. What remains is not a coherent blueprint but a residual trace that’s been diluted, abstracted, and embedded in the system’s behavior like a homeopathic imprint rather than a guiding principle.

Through this lens, two distinct Dirtscrapers come into view. The first, created with Porpentine before I began working with AI, tolerated gaps and left space for unresolved tensions to shape its meaning over time. The second, developed through AI-assisted processes, experiences failure differently: not through incompleteness, but through the breakdown of initial coherence. Both are landscapes of failure worth noticing: one thrives on ambiguity, the other shows what takes shape as logic decays.

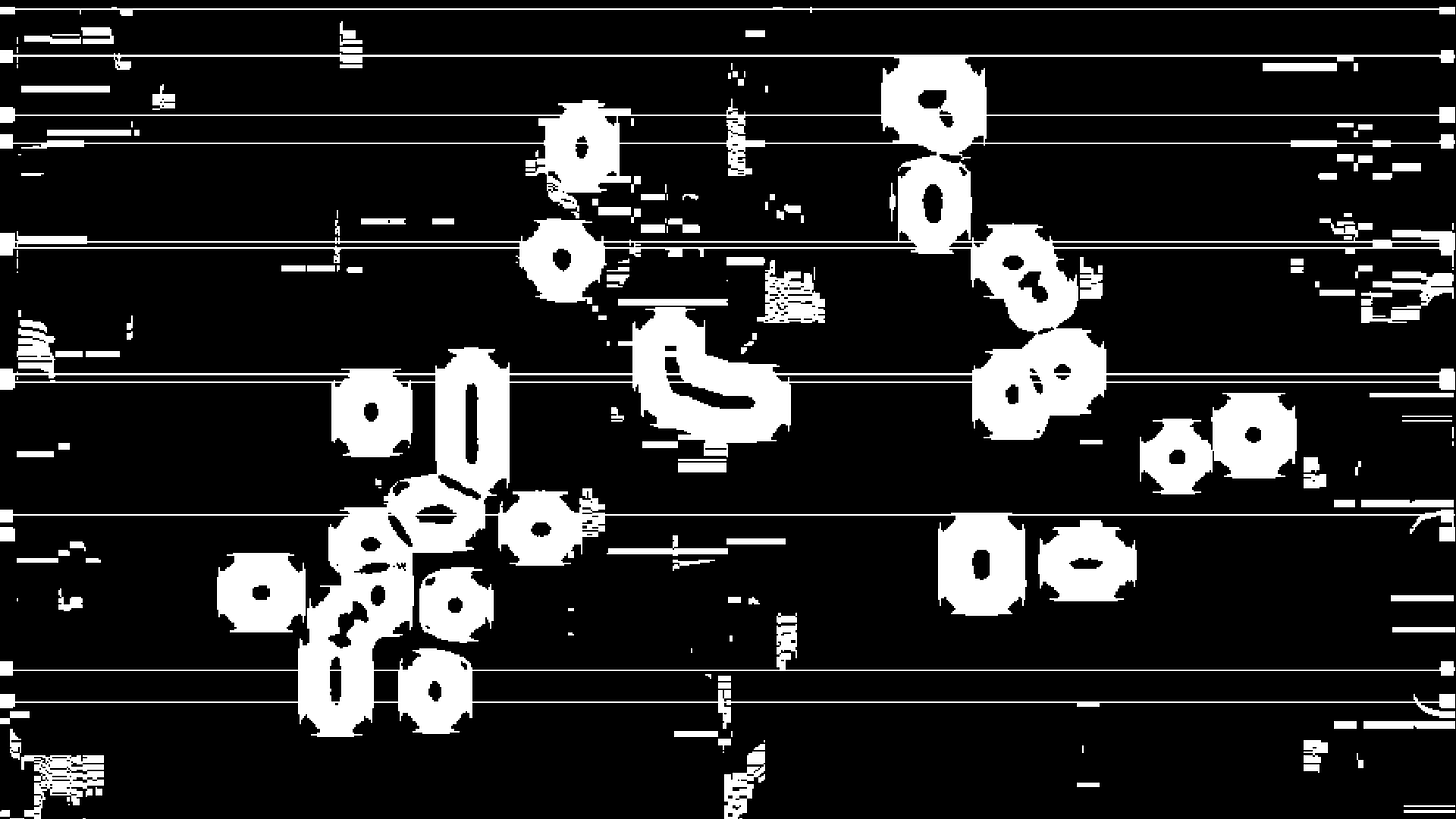

This shift reflects a broader insight into AI-assisted worldbuilding. What begins as the introduction of apparent coherence and control, once achieving a certain scale and density, gives way to a more unstable terrain populated by haunted variants and misaligned outputs. In more colloquial terms, the model produces slop.16 In this way, the Dirtscraper reveals how a world, initially shaped by intentional design, becomes something more unruly, layered, and contingent through its entanglement with generative processes. The Dirtscraper does not simply depict collapse; it enacts it. It renders visible the limits of control and the generative possibilities that can emerge through failure.

REALITY GLITCHES

There are days when I feel like reality is fraying around the edges. I'll misread an advertisement pretending to be a news story or scroll past an image that seems real until I notice the telltale smears of a latent diffusion model’s guesswork. My brain fills in blanks that never existed. So much of my reality looks fake.

This is not new, exactly. Our perception has always been porous. Lately, though, the leaks seem to be widening. Specific words are starting to mean too many things at once. Images are starting to mean nothing at all. The same interface that delivers breaking news also shows me a deep-faked celebrity selling AI-generated supplements, their face eerily convincing. It tells me a meme is real and a real atrocity is a meme. When I try to confirm a photo's origin, I sometimes end up in a recursive swamp of links that all lead back to each other. I no longer trust my own verification reflex.

This breakdown of visual and textual belief has made its way into my imaginary world. In Aria Engine, everything is suspect. The architecture shifts. The signage lies. The smart plastic displays glitch like a replicant blinking too slowly. Aria herself receives notifications from a system that no longer knows who she is. Her STOMA tells her to smile when she's in danger, to sleep when the walls are on fire. The infrastructure is gaslighting her.

This isn't worldbuilding in a traditional sense. It is a way of processing the epistemic vertigo induced by living in a world where AI tools are rapidly destabilizing our relationship to visual and textual truth. When I collaborate with a model to build Aria's world, we are together creating a fictional response to a very real condition: the growing uncertainty about what constitutes real information in a media ecosystem increasingly saturated with synthetic content.

This is no longer a question of authorship, but of ontology. What counts as real when generated content is more coherent than the disjointed texture of actual events? Consider the AI-generated influencers populating so many Instagram feeds.17 They are designed from fragments of real faces and gestures and often combine to evoke more legible emotional responses than candid photographs of my own family and friends. The comments beneath their images, a mixture of bots, humans, and bots mimicking humans, often form a chorus of synthetic longing. This is the condition under which I now create: one in which it feels safer to express desire through an avatar than through an actual face.

In such a context, belief no longer anchors itself to truth. Instead, it attaches to legibility. What is accepted as real is what aligns with the interface, what follows expected patterns, and what avoids flickering too strangely. This creates a significant challenge for my own worldbuilding, which has traditionally thrived on ambiguity. A world that feels alive is not one that is perfectly coherent. It is one that flickers, one that contains gaps and inconsistencies that invite imaginative labor. These irregularities are not flaws to be corrected; they are affordances that make the world feel inhabited rather than rendered. While scholars such as Mark J. P. Wolf have emphasized that successful worldbuilding relies on internal consistency and a sense of completeness, it is equally important to recognize that what feels whole to a reader or player is often sustained through selective omission, strategic ambiguity, and unresolved detail.18 AI-generated outputs, with their tendency toward premature resolution and surface-level coherence, risk displacing this vital tension. Inconsistencies are not flaws; they are openings. They are what make a world feel human made.

The question, then, is what happens when irrationality is treated as error? The Zone of Aria Engine was never meant to be consistent. It was meant to unsettle. As I rely more on generative tools, however, I find myself cleaning the world up to make it more searchable. I have caught myself prompting the model to design environments that look like someone smart made them. The results are always convincing. But they never feel lived-in. They lack what Avery Gordon calls ghostly matters, the presence of that which cannot be assimilated into rational design.19

This inversion marks a shift in how we locate reality. If enough people believe an image, it becomes real. If a rendering is clean enough, it displaces the sketch. The simulation replaces the reference. The model replaces the memory. In this world, fiction must work harder to remain strange. Deepfakes may signal a threat to political trust, but the deeper risk is aesthetic: that we will forget what fiction is supposed to feel like: incomplete and unstable.

To build a world under these conditions requires a return to uncertainty. It demands an aesthetics of disbelief. The challenge is not to reject the simulation, but to make space within it for the unresolved. The world must look real enough to be legible, but strange enough to be felt. It must blink too slowly. It must breathe against the rhythm of the machine. It must remind us that the unbelievable lives here too.

AFTER THE PROMPT

I don't want to reject the models. I still use them. I build with them. They've reflected me, inspired me, even clarified things I couldn't name. But I do want to resist the seduction of speed. I want to remember that worldbuilding, at its best, isn't a response to a prompt. Good worldbuilding is the long unfolding of a question that stays stuck in my mind even after I try to resolve it. That kind of worldbuilding doesn't come clean. It arrives tangled, contradictory, and full of noise. It hides things on purpose. Working inside Aria Engine has shown me that the best ideas often emerge in friction: a structural contradiction, a mechanic that doesn't quite click, an image I can't render but can't stop imagining. These frictions are not bugs. They're the stories that drive the world.

The model’s power lies in its anticipatory logic. It wants to help, and it often does. But help can become a form of overreach. In addition to asking what the model can offer, I ask what is lost in the exchange. I consider what remains hidden within the coherence it provides, and what contradictions are excluded when it tries to complete a thought on my behalf. In developing Aria Engine, I have found that the most generative use of AI does not come from avoiding the tool, but from engaging it in ways that sustain creative heat. These are moments when the output resists resolution, when something arrives unfinished and must be held open rather than accepted. This is not resistance for its own sake. It is a practice of attunement. It means noticing what the model misses and staying with what does not yet make sense. What interests me now is not fluency, but the density that forms when meaning is delayed, and the warmth that gathers just before coherence takes hold.

The future of collaborative worldbuilding with AI may depend less on technical capacity than on our ability to remain attentive within systems that increasingly flatten distinction. The model generates not only content, but a grammar of expectation for a world that is legible before it is imagined. This legibility can feel like relief, but it also carries a kind of epistemic foreclosure. In my own practice, I have noticed how the creative turbulence that once signaled the beginning of something has become harder to access. Scenes arrive finished. Narrative logics replicate faster than I can revise any single one.

To work within these systems is to risk losing track of what belongs to you or of what you can hold in your head at once. The most generative stance may not be one of control or mastery. It may require careful disorientation instead. It asks for a willingness to let the tool produce more than you can immediately absorb, to dwell in what does not yet make sense, and to treat that lag between generation and understanding as a productive space for creation. Because what I want now is not a finished world. I want the heat that rises when something alive disintegrates in my hands.

REFERENCE

Barthes, Roland, "The Pleasure of the Text" (New York: Hill and Wang, 1975).

Bleecker, Julian, "Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction" (Near Future Laboratory, March 2009).

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, "Biographia Literaria", ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 304.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong, "Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media" (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

DeLanda, Manuel, "Philosophy and Simulation: The Emergence of Synthetic Reason" (London: Continuum, 2011)

Doležel, Lubomír, "Heterocosmica: Fiction and Possible Worlds" (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

Fisher, Mark, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater Books, 2016).

Galloway, Alexander R.,” Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization” (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004)

Genette, Gérard, "Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method", trans. Jane E. Lewin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980), 25–27.

Gordon, Avery, "Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination" (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

Harrison, M. John, “What It Is We Do When We Write Science Fiction,” "The New York Review of Science Fiction", no. 216 (August 2006). Reprinted on "The M. John Harrison Blog", April 7, 2007. https://ambientehotel.wordpress.com/2007/04/07/what-it-is-we-do-when-we-write-science-fiction/.

Hayles, N. Katherine, “My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005)

Hergenrader, Trent, "Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers" (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019).

Herman, David, "Basic Elements of Narrative" (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

Jenkins, Henry, "Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide" (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

Manovich, Lev, "The Language of New Media" (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

Manovich, Lev, "Software Takes Command" (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NYU Press, 2009.

Patterson, Troy, “Shudu Gram Is a White Man’s Digital Projection of Real-Life Black Womanhood,” "The New Yorker", May 10, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/shudu-gram-is-a-white-mans-digital-projection-of-real-life-black-womanhood.

Pavel, Thomas G., "Fictional Worlds" (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986).

Purdom, Clayton, “A Brief History of the Zone, the Sci-Fi Idea That Swallows People Whole,” "The A.V. Club", October 16, 2019.

Radford, Alec et al, “Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners,” OpenAI, 2019, https://cdn.openai.com/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf.

Roine, Hanna-Riikka, "Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements: The Rhetoric of Worldbuilding in Contemporary Speculative Fiction" (Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2016).

Ryan, Marie-Laure, "Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media" (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Ryan, Marie-Laure, “Story/Worlds/Media: Tuning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology,” in "Storyworlds Across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology", ed. Marie-Laure Ryan and Jan-Noël Thon (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 25–49.

Ryan, Marie-Laure and Jan-Noël Thon, eds., "Storyworlds Across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology" (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

Soleri, Paolo. Arcology: The City in the Image of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970.

Tremblay, Kaitlin, "Collaborative Worldbuilding for Video Games" (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2023).

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, "The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins" (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Vaswani, Ashish et al., “Attention Is All You Need,” in "Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems" 30 (2017): 5998–6008.

Wolf, Mark J. P., "Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation" (New York: Routledge, 2012).

Wolf, Mark J. P., ed., "Revisiting Imaginary Worlds: A Subcreation Studies Anthology" (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Wolf, Mark J. P. “Artificial Intelligence and the Possibility of Sub‑Subcreation.” In Navigating Imaginary Worlds: Wayfinding and Subcreation, edited by Mark J. P. Wolf, 240-253. New York – London: Routledge, 2025.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge distinguishes Fancy from Imagination in Biographia Literaria, describing Fancy as a mechanical faculty that merely assembles preexisting materials without altering their essence. See Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 304.

Lubomír Doležel, Heterocosmica: Fiction and Possible Worlds (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 169. Doležel outlines how the texture of a fictional world results from authorial choices, distinguishing between explicit texture (fictional facts) and zero texture (gaps). He emphasizes that gaps are a necessary and universal feature of fictional worlds, and draws on related insights from Thomas Pavel, Marie-Laure Ryan, and Lucien Dällenbach regarding how different literary traditions and historical moments approach incompleteness.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 1. Chun argues that the power of new media lies in their capacity to become habitual, noting, “We update in order to remain the same, to reinforce habits rather than break them.”

Alexander R. Galloway, Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004). Galloway theorizes protocol as a foundational logic of control in digital networks, arguing that even decentralized systems are governed by technical rules that structure interaction and constrain possibility.

M. John Harrison, “What It Is We Do When We Write Science Fiction,” The New York Review of Science Fiction, no. 216 (August 2006). Reprinted on The M. John Harrison Blog, April 7, 2007. https://ambientehotel.wordpress.com/2007/04/07/what-it-is-we-do-when-we-write-science-fiction/.

Thomas G. Pavel and Marie-Laure Ryan both argue that fictional worlds are defined as much by what they omit as by what they include. In Fictional Worlds, Pavel emphasizes that fictional universes are necessarily incomplete, structured through selective emphasis and interpretive gaps that invite symbolic projection. Similarly, in Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory, Ryan theorizes degrees of incompleteness as fundamental to fictional world models. She distinguishes genres and literary periods by how they manage textual silence, contrasting realism’s illusion of mimetic fullness with modernism’s embrace of fragmentation and absence. See Thomas G. Pavel, Fictional Worlds (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), 108–9; Marie-Laure Ryan, Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 131–34.

Trent Hergenrader, Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 50–52.

Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, trans. Jane E. Lewin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980), 25–27.

Hanna-Riikka Roine, Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements: The Rhetoric of Worldbuilding in Contemporary Speculative Fiction (Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press, 2016), 176–178.

Clayton Purdom, “A Brief History of the Zone, the Sci-Fi Idea That Swallows People Whole,” The A.V. Club, October 16, 2019. Purdom traces the cultural lineage of the “Zone” as a recurring motif in science fiction, from Stalker to Annihilation. He describes it as a space defined by instability, contradiction, and transformation. The Zone functions less as a setting than as a condition that resists narrative containment and consumes those who enter.

Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater Books, 2016), 15–16.

Julian Bleecker, Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction (Near Future Laboratory, March 2009), https://blog.nearfuturelaboratory.com/2009/03/17/design-fiction-a-short-essay-on-design-science-fact-and-fiction/.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

Paolo Soleri coined the term "arcology" to describe a fusion of architecture and ecology: high-density, self-sustaining urban structures designed to minimize environmental impact. See Paolo Soleri, Arcology: The City in the Image of Man (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970).

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 17–18.

“Slop” is a colloquial term used to describe AI-generated content that is syntactically fluent but semantically hollow. It refers to an accumulation of language fragments that gesture toward meaning without fully achieving it, often producing the illusion of coherence while lacking depth or intentionality.

Troy Patterson, “Shudu Gram Is a White Man’s Digital Projection of Real-Life Black Womanhood,” The New Yorker, May 10, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/shudu-gram-is-a-white-mans-digital-projection-of-real-life-black-womanhood.

Mark J. P. Wolf, Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (New York: Routledge, 2012), 33.

Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 8. Gordon uses the term “ghostly matters” to describe the lingering presence of unresolved histories, absences, and social forces that continue to shape lived experience despite being officially unacknowledged or invisible.

Long live weird fiction, failure and friction. Great piece.